The Piketty Challenge:

Global Inequality and World Revolutions*

Pachamama

Christopher Chase-Dunn

Institute for Research

on World-Systems

University of

California, Riverside, Riverside, CA. 92521

www.irows.ucr.edu

10413 words, v. 1-21-16

Forthcoming in Lauren Langman and David A. Smith (eds.) Twenty-first Century Inequality: Marx, Piketty and Beyond., Brill

This is IROWS Working Paper #101 at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows101/irows101.htm

*

Thanks to Evan Heimlich and Hiroko Inoue for helpful comments on an earlier

draft.

Abstract: This chapter discusses

the inequality trends revealed by Thomas Piketty’s research as context for a

consideration of transnational social movements of the past and in the current

era. Social movements and world revolutions have restructured global governance

institutions over the past several centuries. The rebellions, protests and

counter-hegemonic regimes that have emerged since the 1990s need to be compared

with earlier world revolutions in order to assess the prospects for the future

emergence of a more coherent effort to transform the capitalist world-economy

into a democratic and collectively rational global commonwealth.

Thomas Piketty’s (2014) research on

changes in the magnitude of wealth and income inequalities within several core

countries over the past 200 years is a major contribution to the study of

economic inequalities because he uses data from tax returns that are more

reliable than the usual household surveys on income and that allow the close

study of the wealth and incomes of the very rich. His results show a long-term

trend toward lesser and then greater inequality within core countries (the so-called

“great u-turn”) as well as important similarities and differences between them.

He shows that the returns to wealth and labor have changed greatly as a result

of the rise, and partial demise, of the welfare state. He also discusses the

issue of distributive justice within national societies, and he argues in favor of a global

progressive tax on wealth that would help redistribute income.

The

main lacuna in Piketty’s work that I will address in this chapter is the lack

of attention to the role that social movements played in the causation of the

inequality trends that he finds and the possibilities for social movements to

once again challenge the growing inequality trends of the past several decades.

Piketty’s analysis does not get at the

roots of the problems of global capitalism. The important political and

analytical task is to distinguish between those institutional and structural

aspects of the contemporary world-system that are congruent with a more

egalitarian and sustainable future global society and those that are not.

The

world-systems perspective

The world-systems perspective presents a

structural interpretation of the cycles and trends that have constituted the

expansion and evolution of global capitalism (Wallerstein 2011; Arrighi 1994; Chase-Dunn and Lerro

2014). This holistic structural approach allows us to see both the similarities

and the important differences between the current world historical period and

earlier periods that were similar in some ways but different in others. The

expansion and deepening of capitalism has occurred in the context of the rise

and fall of hegemonic core powers, waves of colonization in which European

powers subjugated and exploited most of Asia, the Americas and Africa, and the

waves of decolonization that extended the European system of formally sovereign

states to the non-core. The expansion and deepening of capitalist production

and the increasing size of the nation-states that played the role of hegemons

were driven and made possible by movements of resistance that were located both

within core polities and, importantly, in the non-core. Each of the hegemons

(the Dutch in the l7th century, the British in the 19th century and

the United States in the 20th century) were formerly semiperipheral states that rose to core status in struggles

with contending great powers. Their successes were partly based on their

abilities to deal with resistance from below more effectively than their

competitors (Wallerstein 1984).

It is important to accurately grasp both the structural similarities and differences between the current world historical period and earlier periods that were similar but also importantly dissimilar. The United States has been in decline in terms of hegemony in economic production since 1945 and this has been similar in many respects to the decline of British hegemony in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Chase-Dunn et al 2011). Giovanni Arrighi (2006) noted that the period of British hegemonic decline (1870-1914) moved rather quickly toward conflictive interimperial rivalry because economic competitors such as Germany and Japan were able to develop powerful military capabilities that could be used to challenge the British. The U.S. hegemony has been different in that the United States ended up as the single superpower after the demise of the Soviet Union. Some economic challengers (Japan and Germany) cannot easily play the military card because they are stuck with the consequences of having lost the last World War. This, and the immense size of the U.S. economy, will probably slow the process of hegemonic decline down compared to the rate of the British decline.

The

post-World War II wave of trade globalization and financialization

faltered in 2008 but seems to have recovered since then. A future trough of

trade deglobalization similar to what happened in the

1930s could happen if a perfect storm of calamities and resistance to further

economic globalization should emerge. The declining economic and political

hegemony of the U.S. poses huge challenges for global governance. Newly

emergent national economies such as India and China need to be fitted in to the

global structure of power. The unilateral use of military force by the Bush

administration further delegitimated the institutions

of global governance and provoked resistance and challenges. A similar bout of

“imperial over-reach” in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries on the part of Britain (the Boer Wars) preceded and led to a period

of interimperial rivalry and world war. Such an outcome

is less likely now, but not impossible.

These developments parallel, to some extent, what happened a century ago, but the likelihood of another “Age of Extremes” or a Malthusian correction such what occurred in the first half of the 20th century could be exacerbated by some new twists. The number of people on Earth was only 1.65 billion when the 20th century began, whereas at the beginning of the 21st century there were 6 billion. Moreover, fossil fuels were becoming less expensive as oil was replacing coal as the major source of energy (Podobnik 2006). It was this use of inexpensive, but non-renewable, fossil energy that made the geometric expansion and industrialization of humanity possible.

Now we are facing global warming as a consequence of the spread and rapid expansion of industrial production and energy-intensive consumption. Energy prices have temporarily come down because of fracking and overproduction by countries that are dependent on oil exports, but the low hanging “ancient sunlight” in coal and oil has been picked. “Peak oil” is approaching. “Clean coal” and controllable nuclear fusion remain dreams. The cost of energy will probably go up no matter how much is invested in new kinds of energy production (Heinberg 2004). None of the existing alternative technologies offer low cost energy of the kind that made the huge expansion possible. Many believe that overshoot has already occurred in terms of how many humans are alive, and how much energy is being used by some of them, especially those in the core. Adjusting to rising energy costs and dealing with the environmental degradation caused by industrial society will be difficult, and the longer it takes the harder it will become. Ecological problems are not new, but this time they are on a global scale. Peak oil and rising costs of other resources are likely to cause more resource wars that exacerbate the problems of global governance. The war in Iraq was both an instance of imperial over-reach and a resource war because the U.S. neoconservatives thought that they could prolong U.S. hegemony by controlling the global oil supply. The Paris Agreement on greenhouse gas emissions reached in December of 2015 are good news, but compliance will be difficult, especially for non-core countries.

The first decade of the 21st century has seen a continuation of many large-scale processes that were under way in the last half of the 20th century. Urbanization of the Global South continued as the policies of neoliberalism gave powerful support to the “Live Stock Revolution” in which animal husbandry on the family ranch was replaced by large-scale production of eggs, milk and meat. This, and industrialized farming, were encouraged by the export expansion policies of the International Monetary Fund-imposed Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs). One consequence was the ejection of millions of small farmers from the land. These rural residents had been producing a lot of their own food rather than buying it. A good part of the “increased income” that is counted as poverty reduction in the Global South is due to the monetization of what was formerly agrarian subsistence production. Money incomes and purchases went up but slum-dwellers are no longer able to produce as much of their own food as they did before they migrated to the city. This is one reason why counting monetized income and consumption alone is an imperfect way to study inequality.

For

most of these former rural residents migration to megacities meant moving to

huge slums and gaining a precarious living in the “informal sector” of services

and small-scale production. These huge slums lack adequate water or sewage

infrastructure. The budget cuts mandated by the SAPs, required by the

International Monetary Fund as a condition for further loans, have often

decimated public health systems. And so the slums have become breeding grounds

for new forms of communicable diseases, including new strains of avian flu,

that pose huge health risks to the peoples of both the core and the non-core.

These diseases are rapidly transmitted by intercontinental air travel. Many

public health experts believe that a flu pandemic similar in scope and

lethality to that of the infamous 1918 disaster is highly likely to occur in

the near future (Crosby 2007). Most of the national governments have failed to

adequately prepare for such an eventuality, and so a massive die-off could

easily occur. Like most disasters, the lethality would be much greater among

the poor, especially in the megacities of the Global South (Davis 2005).

In

addition to the lack of attention to the roles of past and future social

movements, there are other lacunae in Piketty’s analysis as well as his

prescriptions. Whereas he mentions global

inequality, his actual research is about trends within core societies. This

is because taxation data over long time

periods is not currently available for most of the non-core countries. But

there is a large and contentious research literature about inequality trends in

the global system as well as an important and consequential set of publically

held assumptions about these trends. Many, including Bill Gates, simply assume

that global inequality has decreased because of rapid economic growth in China

and India in the past several decades. Many critics of capitalist globalization

assume that global inequality must be going up over the past decades because of

Piketty’s findings and because problems of poverty and dispossession in the

Global South are well-known. The problem

is that both within-county and between-country trends need to be taken into

account in order to know the true trend in income distribution for the whole

population of the Earth. And there are difficult issues regarding the

conversion of national currencies into a single global metric (usually U.S.

dollars). A conservative estimate based

on the contentious quantitative literature on trends in global income

inequality is that global inequality increased greatly during the 19th

century industrial revolution and it has remained at about the same high level

or possibly decreased slightly since then (Bornschier

2010). Though the magnitude of global

income inequality expanded in the 19th century, there were already

important amounts of political inequality that had emerged between the core and

the periphery as a result of European colonialism. And these structures were

both outcomes of, and causes of, resistance and rebellions that occurred within

the European core and in the colonized regions.

World

Revolutions

The institutional changes

that have occurred with the rise and fall of the hegemonic core powers over the

past four centuries have constituted a sequence of forms of world order that

evolved to solve the political, economic and technical problems of successively

more global waves of capitalist accumulation. The expansion of global

production required accessing raw materials to feed the new industries, and

food to feed the expanding populations (Bunker and Ciccantell

2004). As in any hierarchy, coercion is a very inefficient means of domination,

and so the hegemons sought legitimacy by proclaiming leadership in advancing

civilization and democracy (the Gramscian side of

hegemony). But the terms of these claims were also employed by those below who

sought to protect themselves from exploitation and domination. And so the

evolution of hegemony was produced by elite groups competing with one another

in a context of successive powerful challenges from below. World orders were

contested and reconstructed in a series of world revolutions that began with

the Protestant Reformation (Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2000: 53-64; Linebaugh and Redicker 2000).

The

idea of world revolution is a broad notion that encompasses all kinds of acts

of resistance to hierarchy, regardless of whether or not they are coordinated

with one another, but that occur relatively close to one another in time.

Usually the idea of revolution is conceptualized on a national scale in which

new social forces come to state power and restructure social relations. When we

use the revolution concept at the world-system level a number of changes are

required. There is no global state (yet) to take over. But there is a global

polity, a world order, which has evolved as outlined above. It is that world

polity or world order that is the arena of contestation within which world

revolutions have occurred and that world revolutions have restructured.

Boswell and Chase-Dunn (2000) focused on those

constellations of local, regional, national and transnational rebellions and

revolutions that have had long-term consequences for changing world orders.

World orders are those normative and institutional features that are taken for

granted in large-scale cooperation, competition and conflict. Years that

symbolize the major world revolutions after the Protestant Reformation are

1789, 1848, 1917, 1968 and 1989. Arrighi, Hopkins and

Wallerstein (2011) analyzed the world revolutions of 1848, 1917, 1968 and 1989

(see also Beck 2011). They observed that the demands put forth in a world

revolution do not usually become institutionalized until a later consolidating

revolt has occurred. So the revolutionaries appear to have lost in the failure

of their most radical demands, but enlightened conservatives who are trying to

manage hegemony end up incorporating the reforms that were earlier radical

demands into the current world order in order to cool out resistance from

below. It is important to tease out the similarities and the differences among

the world revolutions in order to be able to accurately assess the contemporary

situation and to learn from the past. The contexts and the actors have changed

from one world revolution to the next.

This view of the modern

world-system as constituting an arena of political struggle over the past

several centuries implies that global civil society (Kaldor

2003) has existed all along. Global civil society includes all the actors who

consciously participate in world politics. In the past it has consisted

primarily of statesmen, religious leaders, scientists, financiers, and the

owners and top managers of chartered companies such as the Dutch and British

East India Companies. This rather small group of people already saw the global

arena of political, economic, military and ideological struggle as their arena

of contestation (Chase-Dunn and Reese 2011). There has been a “global left” and

transnational social movements involving non-elite actors at least since the

world revolution of 1789.[1] While global civil society is still a

small minority of the total population of the earth, the falling costs of communication

and transportation have enabled more and more non-elites to become

transnational political actors.

Our discussion below focuses

on what Santos (2006) has called the New Global Left and compares it with

earlier incarnations of the global left. This is part, but not all of global

civil society. Other important actors are the forces organized around the World

Economic Forum, the new conservative and neo-fascist elements (Anderson, 2005)

the BRICs (Bond 2013) and the jihadists (Moghadam

2009).

We are in the midst of

another world revolution now. Chase-Dunn and Niemeyer (2009) have called it the

world revolution of 20xx (because it is not yet clear what the key symbolic

year should be). They claim that it began with the anti-International Monetary

Fund riots in the 1980s and the Zapatista revolt in Southern Mexico in 1994.[2]

World

revolutions are hard to study and difficult to compare with one another because

they are complex constellations of events. The time periods and places to

include (and exclude) are hard to judge.

They each have had different mixes of social movements, rebellions and

revolutions, including reactionary movements, and have occurred unevenly in

time and space. What have been the

actual and potential bases for cooperation and competition across the

progressive (antisystemic) movements? How did some of

the movements affect the others? And how

did they relate to the similar and different terrains of power and economic

structures in the world-system at the time that they emerged? And how have they

affected the struggles among elites in their efforts to maintain their

positions or gain new advantages?

The

World Revolution of 20xx

It

is difficult to pick a symbolic year that expresses the main characteristics of

the current world revolution because it is still in formation and it is not

clear which characteristics to pick. The

wave of protests that began with the Arab Spring in 2011 demonstrated some

coherence with regard to their local and global causations, and so some have

concluded that 2011 is a good choice. The Arab Spring was followed by an

anti-austerity summer in Greece and Spain and then the Occupy movement in the

Fall. But it is probably too soon to pick a symbolic year for the current world

revolution.

Some

claim that the anti-International Monetary Fund riots of the 1980s (Walton and

Seddon 1994) were the first skirmishes of the revolts and rebellions against

neoliberal corporate capitalism (Podobnik 2003. [3]

The Zapatista rebellion of 1994 was the first to name neoliberalism as

the enemy. The “Battle of Seattle” in

1999 brought the “antiglobalization movement” to the

attention of large numbers of people. The founding of the World Social Forum

(WSF) in 2001, a reaction to the exclusivity of the World Economic Forum held

in Davos, Switzerland since 1971, provoked the coming together of a movement of

movements focused on issues of global justice and sustainability. The social

forum process has spread to all the regions of the world despite, and because

of, the events of September 11, 2001 and subsequent military adventures carried

out by the neoconservative Bush regime in the United States.

Many of the participants in the contemporary movement of movements are unaware, or are only vaguely aware, of the historical sequence of world revolutions. But others are determined not to repeat what are perceived to have been the mistakes of the past. The charter of the World Social Forum does not permit participation by those who attend as representatives of organizations that are engaged in, or that advocate, armed struggle. Nor are governments or political parties supposed to send representatives to the WSF.[4] There is a great emphasis on diversity and on horizontal, as opposed to hierarchical, forms of organization. And the wide use of the Internet for communication and mobilization makes it possible for broad coalitions and loosely knit networks to engage in collective action projects. The movement of movements at the World Social Forum engaged in a manifesto/charter-writing frenzy as those who sought a more organized approach to confronting global capitalism and neoliberalism attempted to formulate consensual goals and to put workable coalitions together (Wallerstein 2007).

One continuing issue has been whether or not the World Social Forum itself should formulate a political program and take formal stances on issues. The Charter of the WSF explicitly forbids this and a significant group of participants strongly supports maintaining the WSF as an “open space” for debate and organizing. A survey of 625 attendees at the World Social Forum meeting in Porto Alegre in 2005 asked whether the WSF should remain an open space or should take political stances. Exactly half favored the open space idea (Chase-Dunn, Reese, Herkenrath, Alvarez, Gutierrez and Kim 2008). So trying to change the WSF Charter to allow for a formal political program would be very divisive.

But this is not necessary. The WSF Charter also encourages the formation of new political organizations. So those participants who want to form new coalitions and organizations are free to act, as long as they do not do so in the name of the WSF as a whole. In Social Forum meetings at the global and national levels the Assembly of Social Movements and other groups have issued calls for global action and political manifestoes. At the end of the 2005 meeting in Porto Alegre a group of nineteen notable intellectuals and activists issued a statement that was purported to be a consensus of the meeting as a whole. At the 2006 “polycentric” meeting in Bamako, Mali a somewhat overlapping group issued a manifesto entitled “the Bamako Appeal” at the beginning of the meeting. The Bamako Appeal was a call for a global united front against neoliberalism and United States neo-imperialism (see Sen et al 2006). And Samir Amin, the famous Egyptian Marxist economist and one of the founders of the world-systems perspective, wrote a short essay entitled “Toward a fifth international?” in which he briefly outlined the history of the first four internationals (Amin 2006). Peter Waterman (2006) proposed a “global labor charter” and a coalition of womens’ groups meeting at the World Social Forum have produced a feminist global manifesto that tries to overcome divisive North/South issues (Moghadam 2005, 2009).

There has been an impasse in the global justice movement between those who want

to move toward a global united front that could mobilize a strong coalition

against the powers that be, and those who prefer local prefigurative,

horizontalist actions that abjure formal

organizations and refuse to participate in “normal” political activities such

as elections and lobbying. Horizontalism abjures

hierarchical organization and prefers flexible networks without formal

organization (but see Freeman 1970).

Prefiguration is the idea that individuals and small groups can

willfully constitute more humane and egalitarian social relations in the

present. It has a long history as utopian socialism (Engels 1918) and communes, and was an

important component of the Occupy movement’s construction of face-to-face

participatory democracy (Graeber 2013) and has strong

support in the social forum process (Juris 2008, Pleyers

2010). Some of this horizontalism and prefiguration

was inherited from similar tendencies in the world revolution of 1968. Arrighi, Hopkins and Wallerstein (2011: 37-8) pointed out

that the New Left of the sixties embraced direct democracy, attacked

bureaucratic organizations, and was itself resistant to the creation of new

formal organizations that might act as instruments of revolution. These

organizational predilections were seen as the important lessons learned from

earlier waves of class struggle and decolonization. As Arrighi,

Hopkins and Wallerstein (2011:64) pointed out:

… the class struggle “flows out” into a

competitive struggle for state power. As this occurs, the political elites that

provide social classes with leadership and organization (even if they sincerely

consider themselves “instruments” of the class struggle) usually find that they

have to play by the rules of that competition and therefore must attempt to

subordinate the class struggle to those rules in order to survive as

competitors for state power.

In

later years many 68ers joined prefigurative communes

or formed new Leninist organizations, some which have survived (e.g. the Revolutionary

Communist Party, 2010). The resistance to politics as usual, especially

competing for state power, has been very salient in the world revolution of

20xx. These proscriptions are based on the critique of the practices of earlier

world revolutions in which labor unions and political parties became bogged

down in short-term and self-interested struggles that then reinforced and

reproduced the global capitalist system and the interstate system. This

abjuration of formal organizations and participation in institutionalized

political competition is strongly reflected in the constitution of the World

Social Forum as discussed above. And the same elements were robustly present in

the Occupy movement as well as in the several popular revolts that have

constituted the Arab Spring and the other anti-austerity movements (Mason

2013).

Journalist Paul Mason (2013) spent

the last decade doing ethnographic immersion in the wave of protests that occurred

in the Middle East, Spain, Greece, Turkey and the Occupy movement. His

sympathetic analysis of the current world revolution contends that the social

structural basis for horizontalism and anti-formal

organization, beyond the reaction to the reformist outcomes of earlier efforts

of the Left, is due to the presence of a large number of middle-class students

in the protests that were building in the first decade of the 21st

century (see also Korotayev and Zinkin

2011; Milkman, Luce and Lewis 2013; Curran, Schwarz and Chase-Dunn 2014). Of

course, the world revolution of 1968 was also composed of an activist element

within the large stratum of college students who had emerged on the world stage

with the global expansion of higher education since World War II.[5]

Precariat

Fractions

Mason (2013) makes an interesting

comparison of the recent protest wave with the world revolution of 1848, in

which a large number of the activists were also educated, but underemployed,

students. He notes that the participants in the recent wave of protests

were heavily composed of highly educated

young people who were facing the strong likelihood that they will not be able

to find jobs that are commensurate with their skills and certification levels.

Many of these “graduates with no future” have gone into debt to finance their

education, and they are alienated from politics as usual and enraged by the

failure of global capitalism to continue the expansion of middle-class jobs.

Mason notes that the urban poor, especially in the Global South, and workers

whose livelihoods have been attacked by globalization, have also been important

constituencies in the protests. And he points to the significance of the

Internet, social media and cell phones for allowing disaffected digital youth to

organize large protests. He sees the netizens’ “freedom to tweet” as an

important element in a strong desire for individual freedom that is an

important driver of those middle class graduates who have enjoyed confronting

the powers-that-be. This embrace of individuality may be another reason why the

movements have been reticent to develop their own formal organizations and to

participate in traditional organized political activities.

Guy Standing (2011) has undertaken a

broad consideration of how the neoliberal globalization project has affected

global class relations and the nature of work. Standing does not focus on the

nature of the recent protest wave, but his observations and claims overlap

with, and in some ways diverge from, those of Paul Mason. Standing claims that

the reorganization of production that David Harvey (1989) calls flexible

accumulation has produced the recent rise of what he calls the precariat.

Standing sees the rise of precarious labor as constituting a new class, the

precariat, which is significantly different from the proletariat. Employment is

increasingly temporary and workers have

little identification with their jobs or the firms that pay them. The

increasing power of capital, deindustrialization of the core and attacks on labor

unions have produced a reorganization of the global class structure around

precarious work. Standing notes that there are important differences between

different sectors of the precariat. The

slum-dwellers in the informal sector in megacities of the Global South have

long been exposed to precarious labor, though this group has expanded as a

result of the neoliberal transformation of agriculture discussed above. The

over-educated, under-employed are young people from working class and middle

class backgrounds who also face a precarious livelihood, but with rather

different tastes and interests from the folk of the planet of slums. They are

individualistic and difficult to organize using the methods that worked fairly

well for the industrial proletariat.

Standing wants to forge political

alliances among these different groups in order to press for workers rights and

greater protections from states, but he recognizes that this effort faces very

difficult obstacles. Standing also has a very different attitude toward the

“freedom to tweet” than does Mason. He believes that the short attention span

produced by constant exposure to electronic communications makes it difficult

for the young to develop an understanding of the larger historical context in

which the precariat is emerging.

Tweeting makes you stupid, according to Standing. He is rather less

sympathetic with these aspects of the millennials than is Mason, but they both

agree that these are important characteristics that need to be taken into

account in projects that seek to build larger alliances in order to fight for

workers’ rights.

The Multicentric Network of Leftist Movements

Just

as world revolutions in the past have restructured world orders, the current

one might also do this. But in order for this to happen a significant number of

activists who participate in the New Global Left would need to agree on several

complicated matters:

·

the

nature of the most important contemporary problems,

·

a

vision of a desirable future and

·

judgments

about appropriate tactics and forms of movement organization.

The

Transnational Social Movements Research Working Group at the University of

California-Riverside performed a network analysis of movement ties based on the

responses to a survey of attendees that was conducted at the 2005 World Social

Forum meeting in Porto Alegre, Brazil.[6] This

study examined the structure of overlapping links among movement themes by

asking attendees with which of 18 movement themes they were actively

involved. The choices of those attendees

who declared that they were actively involved in two or more movement themes

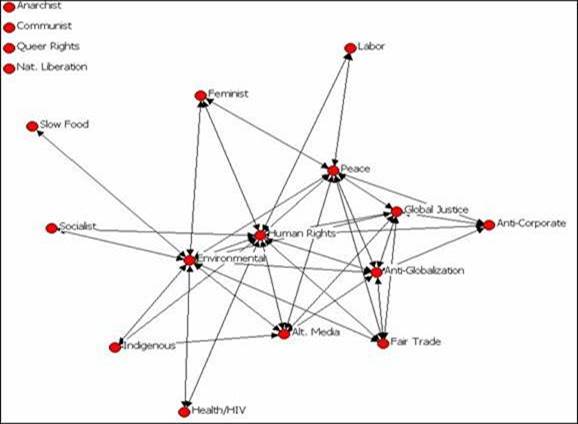

were used to indicate the overlaps among movements. The results show a multicentric network of movement links as illustrated in

Figure 1 (Chase-Dunn, Petit, Niemeyer, Hanneman,

Alvarez, Gutierrez and Reese 2006).  Figure 1: The network of movement

links at the WSF 2005 in Porto Alegre

Figure 1: The network of movement

links at the WSF 2005 in Porto Alegre

All

the movements had some people who were actively involved in other movements.

The four isolates shown in the upper left-hand corner of Figure 1 resulted from

the necessity of dichotomizing the distribution of connections for the purposes

of formal network analysis.

The overall structure of the network of movement linkages reveals a multicentric network organized around five main movements

that served as bridges linking other movements to one another: peace,

anti-globalization, global justice, human rights and environmentalism. These

were also the largest movements in terms of the numbers of attendees who

professed to be actively involved. While no single movement was so central that

it linked all the others, neither was the network structure characterized by

separate cliques of movements that might be easily separated from one another.

Chase-Dunn and Kaneshiro (2009) compared the movement network results found at the 2005 Porto Alegre meeting with the results of a very similar survey carried out at the World Social Forum meeting in Nairobi in 2007. Their findings show a few changes but the main network structure was very similar to that found in Porto Alegre. This suggests that the New Global Left contains a rather stable global network structure of movement interconnections that is largely independent of the location of the meetings. Rather similar network structures were also found at meetings of the U.S. Social Forum in Atlanta in 2007 and in Detroit in 2009 (Chase-Dunn and Breckenridge-Jackson 2013) indicating that the network links among movements seem to be quite similar at the global and national levels, at least for the case of the United States.

This structure means that the transnational activists who participate in the World Social Forum process share many goals and support the global justice framework asserted in the World Social Forum Charter. It also means that the network of movements is relatively integrated and is not prone to splits. A global justice united front that is attentive to the nature of this network structure could mobilize a strong force for collective action in world politics. But there are some obvious problems that need attention.

Global North-South Challenges

Thomas Piketty’s empirical

contribution was to the study of changes in the magnitude of within-country

inequalities, but his prescriptions for solutions included considerations of

inequalities at the global level. The focus on global justice and north/south

inequalities and the critique of neoliberalism provide strong orienting frames

for the transnational activists of the New Global Left (Byrd 2005; Steger,

Goodman and Wilson 2013). But there are difficult obstacles to collective

action that are heavily structured by the huge global inequalities that exist

in the contemporary world-system (Roberts and Parks 2007) and these issues must

be directly confronted.

Our survey of the attendees of the 2005 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre found several important differences between activists from the core, the periphery and the semiperiphery (Chase-Dunn, Reese, Herkenrath, Alvarez, Gutierrez, Kim and Petit. 2008).

Those from the periphery were proportionately fewer, older, and more likely to be men. In addition, participants from the periphery were more likely to be associated with externally sponsored NGOs, rather than with self-funded Social Movement Organizations (SMOs) or unions. NGOs have greater access to travel funds and were able to bring more representatives from the peripheral countries. Survey respondents from the Global South (the periphery and the semiperiphery) were significantly more likely than those from the Global North (the core) to be skeptical about creating or reforming global-level political institutions and were more likely to favor the abolition of existing global institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank (Chase-Dunn et al 2008).

This skepticism probably stems from the historical experience of peoples from the non-core with colonialism and global-level institutions that claim to be operating on universal principles of fairness, but whose actions have either not solved problems or have made them worse. These “new abolitionists” pose strong challenges to both existing global institutions and to efforts to reform or replace these institutions with more democratic and efficacious ones.

George Monbiot’s Manifesto for a New World Order (2003) is a reasoned and insightful call for radically democratizing the existing institutions of global governance and for establishing a global peoples’ parliament that would be directly elected by the whole population of the Earth.[7] Monbiot also advocated the establishment of a trade clearinghouse (first proposed by John Maynard Keynes at Bretton Woods) that would reward national economies with balanced trade, and that would use some of the surpluses generated by those with trade surpluses to invest in those with trade deficits.[8] And Monbiot proposed a radical reversal of the World Trade Organization regime, which imposes free trade on the non-core but allows core countries to engage in protectionism – a “fair trade organization” that would help to reduce global development inequalities. Monbiot also advocated abolition of the U.N. Security Council, and shifting its power over peacekeeping to a General Assembly in which representatives’ votes would be weighted by the population sizes of their countries.

Monbiot

also noted that the current level of indebtedness of non-core countries could

be used as formidable leverage over the world’s largest banks if all the

debtors acted in concert. This could provide the muscle behind a significant

wave of global democratization. But in order for this to happen the global

justice movement would have to organize a strong coalition of the non-core

countries that would overcome the splits that tend to occur between the

periphery and the semiperiphery. This is far

from being a utopian fantasy. It is a practical program for global

democracy.

The

multiple local, regional and largely disconnected human interaction networks of

the past have become strongly linked into a single global system. The treadmill

of population growth has been stopped in the core countries, and is slowing in

the non-core. The global human population is predicted to peak and to stabilize

in the decades surrounding 2075 at somewhere between nine and twelve billion.

Thus population pressure will continue to be a major challenge for at least

another century, increasing logistical loads on governance institutions. The

exit option is blocked off except for a small number of pioneers who may move

out to space stations or try to colonize Mars. Thus a condition of global

circumscription exists. Malthusian corrections may not be only a thing of the

past, as illustrated by continuing warfare and genocide. Famine has been

brought under control, but future shortages of clean water, good soil,

non-renewable energy sources, and food might bring that old horseman back.

As we have already noted above, huge global inequalities

complicate the collective action problem. First world peoples have come to feel

entitled, and non-core people want to have their own cars, large houses and

electronic gadgets. The ideas of human rights and democracy are still

contested, but they have become so widely accepted that existing institutions

of global governance are illegitimate even by their own standards. The demand

for global democracy and human rights can only be met by reforming or replacing

the existing institutions of global governance with institutions that have some

plausible claim to represent the will and interests of the majority of the

world’s people. That means democratic global state formation (Chase-Dunn and

Inoue 2012), although most of the contemporary protagonists of global democracy

do not like to say it that way.

Individualism in the World Revolution

The relationship between

individualism, sociocultural evolution and modernity is a long story, but Paul

Mason’s claim that a new level of individual freedom is an important element in

the recent global wave of protests brings this issue once again to the center

of the discussion about the nature of the New Global Left.[9]

It is also raised by David Graeber’s (2011) assertion

of the individual’s right to self-assess the question of social debt and by

Mary Kaldor’s (2003) defense of the individual’s

right to not participate in politics. Many would agree with the horizontalists and anarchists that the attack on

individualism that was waged by communists and some socialists in the world

revolution of 1917 and its aftermath was a mistake. Individualism is rightly

associated with capitalist modernity, but arguably it is one of the good things

that modernity has brought. The rise of a global human rights regime since

World War II (Brisk 2005; Meyer 2009) and the centrality of the human rights

movement theme within the network of movements found at the World Social Forum

also indicate the importance of the issue of individualism in contemporary

world politics.

Of course there are many kinds of individualism, and it has been emerging since the birth of the world religions, and before (Chase-Dunn and Lerro 2013). Norman Cohn’s (1970) study of European medieval millenarianism describes the Free Spirits, a movement of self-deification in which individual mystics became convinced that they had attained omniscience and omnipotence and were thus entitled to do whatever they wanted, irrespective of the consequences of their acts for others. Ethical egoism denies any obligation to act in the interests of others (e.g. Ayn Rand 1957). The freedom to express one’s unique self in artistic works and in consumer choices are the relatively mild forms of individualism that have become widely accepted by both those who have opportunities to express themselves and by most of those who wish that they could. Individualism that allows great choice, but that does not countenance harming or constraining the actions of others, is not a bad thing whether or not it is engrained in biological human nature, as the evolutionary psychologists believe (McKinnon 2005). The construction of more effective forms of collectivism need not attack the individualisms that serve as legitimations for capitalism, nor the forms of individualism that are supported by many of the activists in the emerging New Global Left.

David Graeber’s

(2011) individualism asserts the right of each person to decide regarding the

issue of social debt – what one owes others, society and nature.[10]

Graeber points out that socialists and communists

(and almost all other authorities) set up systems that justified policies of

distribution and power based on assumptions about debt. Graeber

rejects these, and many would agree with him. Beyond this assumption of

individual authority over the matter of debt, Graeber

presumes natural human tendencies toward sociability, sharing and friendship.

And he contends that the techniques of direct decision-making that constituted

the processes developed by the Occupy movement are good guarantees of

individual rights in collective decision-making (Graeber

2013). This is a sympathetic view of

human nature and an attractive version of individualism that acknowledges the

importance of social life, but leaves participation up to the person.

A Global United Front?

As mentioned above, Paul

Mason stressed the importance of unemployed, but educated, youth in the world

revolutions of 1848 and 20xx. Of course scholars of social movements have long

known that oppressed people are usually led by disaffected members of the

middle or upper classes who have some education and resources that can be

devoted to the tasks of movement leadership. But is there more than this to

Mason’s claim? He notes that many middle class radicals in earlier world

revolutions turned against the urban poor and workers when they posed a strong

and radical challenge. Mason attributes part of the defeat of the

revolutionaries in 1848 to the students betrayal of the radical workers in

European cities. Mason contends that one reason why the middle class radicals

in the current wave of global protest have mainly kept their radicalism is

because the urban poor and workers have been relatively quiescent, at least so

far.

We may also wonder how the

differences between now and 1968 will affect the politics of middle class

students. Perceptions of the

availability of future middle class jobs have changed greatly. Most of 68ers

were able to find middle class jobs if they wanted them, whereas the current

crop of highly educated youth are facing a much more constrained job market as

well as mountains of debt incurred in getting their degrees. Mason sees this as

a cause of activism, but others surmise that educational indebtedness may

undermine rebellious courage.

In 2013 Mason guessed that

the wave of protests would likely melt away if the global economy was

successfully reflated, which is what has happened to some extent (see below). Mason

also recounted the story of the 1930s, when the Global Left started off as a

squabbling bunch of ideological purists, but was driven to make broad alliances

in the popular front by the rise of fascism. Mason saw horizontalism

and prefiguration as going nowhere. But he suggested that the Left might be

driven to form a new united front by the emergence of new economic fiascos,

global environmental disasters and by the further rise of neofascism.

Mason (2013:295-6) said:

Up to now, in today’s

crisis, protest has been driven by narratives of hope and outrage, not of fear.

The horizontalists’ self-isolation, indeed self-obsession,

is not the result of a dictated party line, as in the 1930s, but of something

equally strong in today’s conditions; the inner zeitgeist…. As austerity pushes

parts of Europe towards social meltdown, as fascism revives there and as

democracy is eroded, maybe it is this that drives the worker’s movement beyond

the one-day strike and the social movements beyond the temporary occupation of

space, as well as goading the existing parties beyond the comfort zone dictated

by the global order.

At the World Social Forum a somewhat

less ideological approach could involve a greater willingness to collaborate

with progressive national regimes such as that in Bolivia. Mason called for the

radicals to engage in “physical politics,” by which he meant contention for

power within existing institutions. Arguably this is what the New Global Left

must do if it is to have an important impact on the human future. But this

could be done without completely abandoning some of concerns of the 68ers and

the current generation of activists. The new individualism and participatory

democracy could be embraced while also inventing or reinventing more humane and

sustainable forms of collectivism and new modes of participation in

institutional politics. The enhanced

ability to swarm, using social media and the Internet, is a tactic that appeals

to the millennials and that could be coordinated with more populist forms of

participation in electoral politics.

And with regard to

bureaucratization, the oligarchical tendencies of political parties and all

other formal organizations are well known to sociologists of organization. But we

should recall that it was Thomas Jefferson, an 89er, who said that a revolution is needed about

every 20 years. Voluntary associations have gotten much easier to start since

Jefferson’s time.[11]

Many global activists carry neonatal NGOs around with them in their

backpacks. So if the organization you

are currently working with seems to have gotten ossified, you can start a new

one. This is the part of horizontalism and network

organizing that solves the problem of ossified parties and unions. But it also

leads to the proliferation of specialized organizations at a time when the main

challenge is to weave different movements into a larger organizational instrument

with enough muscle to challenge the global powers that be – a party-network.

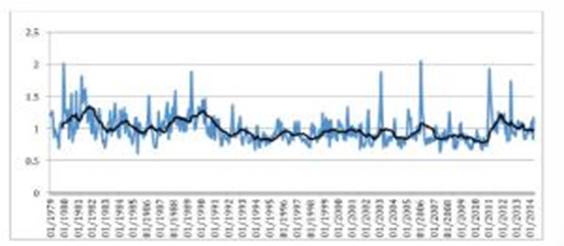

The wave of protests that built up

in the last few decades peaked in 2011 and has declined somewhat since then (Karatasli et al 2015; Carothers and Youngs 2015). The protest intensity measure assembled from

web sources by GDELT (Leetaru 2014) shows successive

waves of global protests from 1979 to 2014

(see Figure 2). The partial decline since 2011 is probably due, in part,

to reflation of the global economy since

the crash of 2008. But the decline probably also reflects the debacles that

have ensued since the Arab Spring, which have understandably reduced the

enthusiasm of idealistic democracy protestors in war zone countries. The Green

Revolution in Iran was suppressed. The tragic events in Egypt and Syria have

been especially disheartening. Horizontalism and

prefiguration seem to presume a Habermasian world of

legitimate and protected political discourse that does not exist in many

regions. Military coups and contending mass parties like the Muslim Brotherhood

leave little room for the protests of the precariat to influence political

discourse. All world revolutions have gone through cycles of activism and

quiescence.

Figure 2 – Intensity of protest activity worldwide 1979-April

2014 (black line is 12-month moving average) (Leetaru 2014)[12]

The protests

mounted by the global justice and anti-austerity movements have changed the

political discourse about inequality and

have helped set the stage for Thomas Piketty’s research to be widely read and

discussed. The current U.S. presidential election campaign has the Democrats

vying with one another over how much to crack down on Wall Street. Podemos, an

anti-austerity party in Spain led by former autonomist Pablo Iglesias Turrion, developed a wide following and gained important

representation in the Spanish election of December 2015. But the debacle of Syriza in Greece, concluding an austerity compromise

despite a popular mandate to stand up against global finance capital, presents

an object lesson for those who have preached the dangers of institutional

politics. The quote above from Arrighi, Hopkins and

Wallerstein (2011:64) seems particularly apt. A valuable opportunity was missed

in Greece to show that indeed there are progressive alternatives to neoliberal

capitalist globalization.

Will the current world revolution

eventually develop enough muscle to challenge neoliberal capitalism and to

provoke enlightened conservatives to usher in a new era of global Keynesianism

that is more sustainable and less polarizing than the capitalist globalization

project? Or will a perfect storm of environmental disaster, hegemonic decline, mass

immigrations, interimperial rivalry, ethnic violence,

and neo-fascism produce so much chaos that a United Front of the New Global

Left will have an opportunity within the next few decades to fundamentally

transform the capitalist world-system into a democratic and collectively

rational global commonwealth? Both of these options would require a United Front

that brings the progressive movements, parties and regimes together.

References

Amin, Samir 2006

“Towards the fifth international?” Pp. 121-144 in Katarina Sehm-

Patomaki and Marko Ulvila (eds.) Democratic Politics Globally. Network

Institute for

Global Democratization (NIGD Working Paper 1/2006),

Tampere, Finland.

Anderson, Perry 2005 Spectrum.

New York: Verso

Arrighi, Giovanni 1994 The Long Twentieth Century London: Verso.

_________________ 2006. Adam

Smith in Beijing. London: Verso

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K. Hopkins and

Immanuel Wallerstein. 2011 [1989]

Antisystemic

Movements. London and

New York: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni and Beverly Silver 1999 Chaos and Governance in the Modern

World-System:

Comparing

Hegemonic Transitions.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press.

Beck, Colin J.

2011 “The world cultural origins of revolutionary waves: five centuries of

European contestation. Social Science History 35,2: 167-207.

Beck, Ulrich

2005 Power in the Global Age. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Bello, Walden

2002 Deglobalization

London: Zed Books.

Benjamin, Medea and Andrea

Freedman 1989 Bridging the

Global Gap: A Handbook

to Linking Citizens of the First and

Third Worlds. Cabin John, MD: Seven

Locks Press.

Bond, Patrick 2012 The Politics of Climate Justice:

Paralysis Above, Movement

Below Durban,

SA: University of Kwa-zulu Natal Press

___________ (ed.) 2013 Brics in Africa: anti-imperialist,

sub-imperialist of in

between? Centre for Civil Society,

University of Kwa-Zulu-Natal.

Bornschier,

Volker 2010 “On the evolution of inequality in the world system”

Pp. 39-64 in Christian Suter (ed.) Inequality Beyond Globalization: Economic Changes,

Social

Transformations and

the Dynamics of Inequality. Zurich: LIT Verlag

Boswell, Terry

and Christopher Chase-Dunn 2000 The Spiral of Capitalism and Socialism:

Toward Global Democracy.

Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Byrd, Scott C. 2005.

“The Porto Alegre Consensus: Theorizing the Forum Movement”

Globalizations.

2(1): 151-163.

Carothers, Thomas and Richard Youngs

2015 The Complexities of Global Protests

Washington,

DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Castells, Manuel 2012 Networks of outrage

and hope : social movements in

the Internet

age Cambridge:

Polity Press

Chase-Dunn,

C. Ian Breckenridge-Jackson 2013 “The

Network of movements in the U.S.

social forum process: Comparing Atlanta 2007

with Detroit 2010” submitted for

publication https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows71/irows71.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. James Fenelon, Thomas D. Hall, Ian

Breckenridge-Jackson and Joel Herrera 2015

“Global Indigenism and

the Web of Transnational Social Movements” IROWS Working Paper #87.

Submitted for publication.

Chase-Dunn,

C., Joel Herrera, John Aldecoa, Ian

Breckenridge-Jackson and Nicolas Pascal

2016 “Anarchism in the web of

transnational social movements” To be presented

at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association,

Atlanta March 16-

19, IROWS Working Paper #104 https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows104/irows104.htm

Chase-Dunn,

Christopher and Hiroko Inoue 2012 “Accelerating democratic global state

formation” Cooperation

and Conflict

47(2) 157–175.

http://cac.sagepub.com/content/47/2/157

Chase-Dunn, Chris, Roy Kwon, Kirk

Lawrence and Hiroko Inoue 2011 “Last of the

hegemons:

U.S. decline and global governance” International

Review of Modern

Sociology 37,1: 1-29 (Spring). https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows65/irows65.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. Christine Petit, Richard Niemeyer, Robert A. Hanneman and

Ellen

Reese 2007 “The contours of solidarity and division among global

movements”

International

Journal of Peace Studies 12,2: 1-15 (Autumn/Winter)

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows26/irows26.htm

Chase-Dunn C. and Matheu Kaneshiro 2009

“Stability and Change in the contours of

Alliances

Among movements in the social forum process” Pp. 119-133 in David

Fasenfest (ed.) Engaging Social Justice. Leiden: Brill. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows44/irows44.htm

Chase-Dunn, Christopher and Ellen Reese 2011 “Global party formation in

world historical

perspective” Pp. 53-91 in Katarina Sehm-Patomaki and Marko Ulvila

(eds.) Global

Party Formation. London: Zed Press. https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows33/irows33.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. and Bruce Lerro

2014 Social Change: Globalization from

the Stone Age to the

Present. Boulder, CO: Paradigm https://www.routledge.com/products/9781612053288

Chase-Dunn,

C. and R.E. Niemeyer 2009 “The world

revolution of 20xx” Pp. 35-57 in

Mathias Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.)

Transnational Political Spaces. Campus Verlag:

Frankfurt/New York

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows35/irows35.htm

Cohn, Norman 1970 The Pursuit of the Millennium. New York: Oxford University Press.

Collins, Randall 2013 “The end of

middle-class work: no more escapes” Pp. 37-70 in

Wallerstein, Immanuel, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derlugian and Craig

Calhoun Does Capitalism Have a Future? New York:

Oxford University Press.

Conway, Janet M. 2013 Edges of Global Justice: The World Social

Forum and Its Others. London:

Routledge.

Crosby, Alfred W. 2007. Infectious

Diseases as Ecological and Historical Phenomena, with

Special

Reference to the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919. Pp. 280-287 in The World

System

and the Earth System: Global Socioenvironmental Change and Sustainability since

the

Neolithic, edited by A. Hornborg

and C. Crumley. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast

Press.

Curran, Michaela, Elizabeth A. G. Schwarz and C Chase-Dunn 2014

“The Occupy

Movement

in California” in Todd A. Comer ed. What Comes After

Occupy?: The

Regional

Politics of Resistance. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows74/irows74.htm

Davis, Mike 2006 Planet of Slums. London: Verso

__________

2005. Monster At Our Door: The Global

Threat of Avian Flu. New York: New

Press.

GDELT Project http://gdeltproject.org/

Engels, Frederick 1918 Socialism: Utopian and Scientific.

Chicago: Charles Kerr.

Evans, Peter B. 2009 “From

Situations of Dependency to Globalized Social Democracy,”

Studies

in Comparative International Development 44:318–336

____________ 2010 “Is it

Labor’s Turn to Globalize? Twenty-first Century opportunities

and

Strategic Responses” Global Labour Journal (1)3:

352-‐379.

Freeman, Jo 1970 “The tyranny of structuralessness”

http://www.jofreeman.com/joreen/tyranny.htm

Galtung, Johan 2009 The Fall of the U.S. Empire – And Then What?: Successors,

Regionalization or

Globalization? U.S. Fascism or U.S. Blossoming? Oslo: Kolofon Press

Gill, Stephen 2000 “Toward a post-modern

prince? : the battle of Seattle as a moment in the

new

politics of globalization” Millennium

29,1: 131-140

Graeber, David 2011 Debt: The First 5000 Years. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

____________ 2013 The Democracy Project: A History, A Crisis, A Movement. New York:

Spiegel

and Grau.

Hardt,

Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2012. Declaration. New York: Argo Navis Author

Services

Harris, Kevan

and Ben Scully 2015 “A hidden counter-movement?: precarity,

politics and

social

protection before and beyond the neoliberal era” Theory

and Society , Volume

44, Issue 5, pp 415-444.

Harvey, David 1989 The

Condition of Postmodernity. London: Blackwell

Heinberg, Richard. 2004. Powerdown. Gabriola Island, BC: Island Press.

Juris, Jeffrey S. 2008 Networking Futures : the Movements Against

Corporate Globalization

Durham, N.C. : Duke University Press

Kaldor, Mary 2003 Global Civil Society. Malden, MA: Polity Press

Karatasli, Savan Savas, Sefika Kumral,

Ben Scully and Smriti Upadhyay

2015 “ Class crisis

and

the 2011 protest wave: cyclical and secular trends in global labor unrest” Pp.

184-200 in Immanuel Wallerstein, C. Chase-Dunn

and Christian Suter (eds.)

Overcoming

Global Inequalities. Boulder, CO:

Paradigm Publishers

Korotayev, A.V., and J.V Zinkina. 2011.

“Egyptian Revolution: A Demographic Structural Analysis.”

Entelequia, Revista Interdisciplinar (13):

139–170.

Did the Arab

Spring Really Spark a Wave of Global Protests?”

Foreign Policy (May 30).

Lindholm, Charles and Jose Pedro Zuquete 2010 The

Struggle for the World. Palo Alto:

Stanford

University Press.

Linebaugh, Peter and Marcus Rediker.

2000. The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners

and

the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Boston: Beacon.

MacPherson,

Robert 2014 “Antisystemic Movements in Periods of

Hegemonic Decline:

Syndicalism in World-Historical

Perspective” Pp. 193-220 in Christian Suter and C.

Chase-Dunn (eds.) Structures of the World Political Economy

and the Future of Global Conflict

and Cooperation. Zurich: LIT Verlag

Markoff, John 2013 “Democracy’s past

transformations, present challenges and future

prospects”

International Journal of Sociology

43,2:13-40.

Martin, William G. et al 2008 Making Waves:

Worldwide Social Movements, 1750-2005. Boulder,

CO:

Paradigm

Mason, Paul 2013 Why

Its Still Kicking Off Everywhere: The New Global Revolutions. London: Verso

McKinnon, Susan 2005 Neoliberal

Genetics: the Myths and Moral Tales of Evolutionary Psychology.

Chicago: Prickly

Paradigm Press.

Milkman, Ruth,

Stephanie Luce and Penny Lewis 2013 “Changing the subject: a bottom-up

account of Occupy Wall Street in New York

City” CUNY: The

Murphy Institute

http://sps.cuny.edu/filestore/1/5/7/1_a05051d2117901d/1571_92f562221b8041e.pdf

Moghadam, Valentine M. 2005 Globalizing Women.

Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University

Press.

__________________ 2009 Globalization

and Social Movements: Islamism, Feminism and the

Global Justice Movement. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

__________________2012 “Anti-systemic Movements Compared.”

In Salvatore J. Babones and

Christopher

Chase-Dunn (eds), Routledge

International Handbook of World-Systems Analysis. New York, NY: Routledge.

Monbiot, George

2003 Manifesto for a New World Order. New York: New Press.

Piketty,

Thomas 2014 Capital in the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press

Pleyers, Geoffrey. 2010. Alter-Globalization. Cambridge, MA: Polity.

Podobnik, Bruce 2006 Global Energy Shifts: Fostering Sustainability in a Turbulent Age.

Philadelphia,

PA: Temple University Press.

Martin, William G. et al 2008 Making Waves:

Worldwide Social Movements, 1750-2005.

Boulder,

CO: Paradigm

Meyer, John W. 2009 World Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rand, Ayn 1957 Atlas Shrugged. New York: New American Library.

Reitan, Ruth 2007 Global Activism. London: Routledge.

Revolutionary

Communist Party 2010 Constitution for the

New Socialist Republic in North America.

Chicago: RCP Publications

Roberts, J. Timmons and Bradley Parks

2007 A Climate of Injustice: global

inequality,

North/South politics and climate

policy. Cambridge, MA: MITPress.

Robinson,

William I. 2004 A Theory of Global Capitalism. Baltimore: MD. Johns

Hopkins

University Press.

________________2014

Global Capitalism and the Crisis of

Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa 2006 The Rise of the Global Left. London: Zed Press.

Schaefer, Robert K. 2014 Social Movements and Global Social

Change: The Rising

Tide. Lanham,

MD: Rowman and Littlefield

Sen, Jai and Madhuresh Kumar with Patrick Bond and Peter Waterman 2007 A Political Programme for the World Social Forum?: Democracy, Substance and Debate in the Bamako Appeal and the Global Justice Movements. Indian Institute for Critical Action : Centre in

Movement (CACIM), New Delhi, India & the University of KwaZulu-Natal Centre for Civil Society (CCS), Durban, South Africa. http://www.cacim.net/book/home.html

Smith,

Jackie, Marina Karides,

Marc Becker, Dorval Brunelle,

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Donatella della

Porta,

Rosalba Icaza

Garza, Jeffrey S. Juris, Lorenzo Mosca, Ellen Reese, Peter Jay Smith and Rolando

Vazquez 2014

Global Democracy and the World Social Forums. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers; Revised 2nd edition.

Smith,

Jackie and Dawn Weist 2012 Social Movement in the World-System. New York: Russell-Sage

Silver,

Beverly 2003 Forces of Labor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Standing, Guy

2011 The Precariat: The New Dangerous

Class. London: Bloomsbury.

___________

2014 A Precariat Charter: From Denizens

to Citizens. London: Bloomsbury

Starr, Amory

2000, Naming the Enemy: Anti-Corporate Movements Confront Globalization.

London:

Zed Press.

Steger, Manfred, James Goodman and Erin K. Wilson 2013 Justice Globalism: Ideology,

Crises,

Policy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tilly, Charles

2007 Democracy. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Turchin, Peter 2010 “Political

instability may be a contributor in the coming decade” Nature 463, 608

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1984

“The three instances of hegemony in the history of the

capitalist world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues

and

Research in Macrosociology, International Studies in Sociology and Social

Anthropology, Vol. 37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Wallerstein, Immanuel 2003 The Decline of American Power. New York: New Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel 2004 World-Systems

Analysis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

________________ 2007 “The World

Social Forum: from defense to offense”

http://www.sociologistswithoutborders.org/documents/WallersteinCommentary.pdf

_________________2011 The Modern

World-System, Volume 4: Centrist Liberalism Triumphant,

1789-1914

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derlugian and Craig

Calhoun 2013 Does Capitalism Have a Future? New York:

Oxford University Press.

Walton, John and David Seddon 1994 Free markets & food riots :

the politics of global adjustment.

Cambridge,

MA: Blackwell.

Waterman,

Peter 2006 “Toward a Global Labor Charter Movement?”

http://wsfworkshop.openspaceforum.net/twiki/tiki-read_article.php?articleId=6