Structural Deglobalization:

A World-Systems Perspective

![]()

Christopher Chase-Dunn, Jisoo Kim and Alexis Alvarez

Institute for Research on World-Systems

University of California-Riverside

<chriscd@ucr.edu>

Draft v. 8-14-20 10832 words, please do not cite without permission.

To be Presented at the virtual meeting of the California Sociological Association, Mission Inn, Nov. 6-7, 2020

This is IROWS Working Paper #137 available at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows137/irows137.htm

The Appendix for this paper is at https://irows.ucr.edu/cd/appendices/deglob/deglobapp.htm

Abstract:

Structural globalization has been both a cycle and an upward trend as periods of greater global integration have been followed by periods of deglobalization on a long-term stair-step toward the greater connectedness of humanity. In the current period the world-system may once again be entering another phase of structural deglobalization as the contradictions of capitalist neoliberalism and uneven development have provoked different kinds of anti-globalization populism and trade wars. This plateauing and possible downturn in economic connectedness is occurring in the context of U.S. hegemonic decline and the emergence of a more multipolar configuration of economic power among states. The combination of greater communications connectivity and greater awareness of North/South inequalities, as well as destabilizing conflicts and climate change in the Global South, have provoked waves of refugee migrations and political reactions against immigrants. The result has been a period of chaos that is similar in some ways (but different in others) with what occurred during the last half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. This paper interrogates the question of whether or not the world-system is indeed once again entering another period of economic deglobalization and compares the current period with what happened in the 19th and 20th centuries to specify the similarities and the differences. We also examine different kinds of recent connectedness to see which kinds are deglobalizing and which kinds are not. And we discuss several theoretical and measurement issues that have emerged from the study of trends of structural economic globalization and deglobalization.

Globalization can be understood as a variable structural characteristic of any network in which long-distance (“global”) links are becoming denser relative to the density of less distant (local) links, or as a proportion of all links. This definition of globalization as large-scale connectedness is similar to Charles Tilly’s definition of structural globalization -- “an increase in geographic range of locally consequential social interactions, especially when that increase stretches a significant proportion of all interactions across international or intercontinental limits” (1995:1–2). Tilly is talking about spatial expansion over time, but a non-expanding network can also become more (or less) globalized if the ratio of long-distance to local links changes.

Structural globalization as an objective variable characteristic of world society is very different from the “globalization project” of capitalist neoliberalism – a political ideology that supports particular policies such as deregulation, privatization, the superiority of market forces and monetization, and attacks on welfare programs and labor unions. The rise of neoliberalism in the 1970s (Reaganism/Thatcherism and the “Washington Consensus”) replaced Keynesian national development as the predominant developmental ideology in local and international contexts (Harvey 2005; McMichael 2017). This is what most people think of as globalization, and the history and current incarnations of this developmental ideology and political program are important subjects for social science, but this paper will mainly focus on the trajectory of structural globalization (connectedness) as an objective variable feature of the world-system.

Systemness is about processes that are important for the reproduction or change of social institutions and social structures. Some of these processes are always local, but the degree to which they involve non-local connections varies over time. Studies of trade networks in world history show a long-term cyclical trend in which relatively long-distance networks rise and fall, but that periodically increase their spatial scale in upsweeps to larger levels, that then oscillate again until the next upsweep. The downswings are periods of trade deglobalization. This paper compares the current period of plateauing and possible deglobalization with earlier plateaus and phases of deglobalization that occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries.[1]

Structural globalization is composed of different kinds of interaction networks that can and should be compared with one another (Chase-Dunn 1999). Economic interaction networks can be compared with political, social, communications, intermarriage, and migration patterns. This paper will mainly focus on types of economic globalization but will also discuss tourism, migration, political globalization, and cultural globalization. We see the modern global world-system as a single integrated structure of connectedness of all the humans on Earth, but we also admit the advantages of comparing different kinds of connectedness with one another and of considering their interactions (e.g. Mann 2012).

Cultural globalization tracks the decline in the number of spoken languages and the emergence of intercultural trade languages and systems of global space and time reckoning, as well as the convergence of local and civilizational cultures toward an emerging global culture (Meyer 2009). Immanuel Wallerstein (2012) called the predominant political ideas that are part of the emerging global culture the “geoculture.”

Political globalization refers to the trajectory of global governance. In the modern world-system global governance has mainly been organized around the hegemony of a series of core states who have provided a degree of order for the whole system, but these hegemons have risen and fallen and so the system periodically experiences a situation of interimperial rivalry and global warfare in which contenders for hegemony have fought it out. The successful hegemons have combined military power with economic power by developing comparative advantages in the production of high technology commodities and the provision of financial services. The hegemons have also proclaimed universalistic ideologies to legitimate the global orders that they have strived to maintain. In addition to global governance by hegemony, since the Napoleonic Wars a set of international organizations have emerged that supplement the system leadership of the hegemons – the Concert of Europe, the League of Nations, and the United Nations system. And the hegemons – the Dutch in the 17th century, the British in the 19th century, and the United States in the 20th century, became successively larger relative to the size of the whole world-system (Wallerstein 1984, Chase-Dunn, Kwon, Lawrence and Inoue 2011). Thus, the rise of international organizations and the increasing relative size of the hegemons have constituted the evolution of global political/military governance. Political deglobalization occurs during periods of interimperial rivalry and nationalistic revival.[2]

The quantitative study of waves of economic deglobalization was begun by Paul Bairoch (1996; Bairoch and Kozul-Wright 1998) and has been taken forward by economic historians who also study recurrent deglobalizations (e,g, O’Rourke and Williamson 2002; O’Rourke 2018).[3] Economic globalization also has several different dimensions that need to be compared with one another. In this paper on deglobalization we will focus mainly on trade and foreign investment, but we will also consider changes in the degree of free trade and protectionism. These are dimensions of economic globalization that can be studied using quantitative indicators based on data sets provided by international institutions. When we began this paper the idea of deglobalization was unpopular among social scientists and in the public. But developments in the last decade such as trade wars, geopolitical competition between the United States and China, the rise of populist authoritarian regimes and increasing nationalism, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic have converted skepticism into a new consensus (World Trade Organization 2020). Nevertheless, we want to be careful with the conclusion that the global political economy has entered a new period of deglobalization. What do the trajectories of measures of economic globalization tell us? Which dimensions are deglobalizing and which are continuing to globalize? And are statistics on trade and investment among nation-states adequate indicators of changes in the degree of integration of the global economy?

The wave of global integration that has swept the world in the decades since World War II can be better understood by studying its similarities and differences with the waves of international trade and foreign investment expansion that have occurred in earlier centuries, especially the last half of the nineteenth century. William I. Robinson’s delineation of a new stage of global capitalism provides important insights about the degree to which the transnational capitalist class has been able to shape global governance in recent decades by repurposing national states to pursue the neoliberal program of privatization, etc., and the high level of transnational financial and production organization that has emerged. But Robinson’s emphasis on the uniqueness of the recent wave of globalization is partly based on his claim that before the emergence of the global capitalism in the last decades of the 20th century the world-system was composed of national economies that were largely autonomous from one another with regard to the circulation of capital (Robinson 2018:55) The world-system perspective contends that the circuits of capital have been organized as an axial division of labor linking the core with the non-core at least since the emergence of the Europe-centered world-system 500 years ago. The circuits of capital began to be globalized in the sixteenth century and there have been waves of increasing globalization of capital since then. Robinson is right to argue that globalization has gone to a new higher level of integration in the recent period, but he does not see that there were earlier waves of integration that were separated by troughs of deglobalization.

Immanuel Wallerstein insisted that U.S. hegemony has been declining for decades. He, and George Modelski (2005), interpreted the U.S. unilateralism of the Bush administration as a repetition of the “imperial over-reach” of earlier declining hegemons that had attempted to substitute military superiority for economic comparative advantage (Wallerstein, 2003). Many of those who denied the notion of U.S. hegemonic decline during what Giovanni Arrighi (1994) called the “belle epoch” of financialization have now come around to Wallerstein’s position in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 and subsequent events. Wallerstein contended that, once the world-system cycles and trends and the game of musical chairs that is capitalist uneven development are considered, the “new stage of global capitalism” does not seem that different from earlier periods. But accurate specification of both the similarities and the differences is important, as we shall see when we compare the earlier periods of deglobalization with what may be happening now.

Measuring Economic Globalization and Deglobalization

Again, structural globalization is a magnitude of the global political economy changes over time. Globalization is an increase in the spatial range of economic interactions, or an increase in the intensity of long-distance economic interactions relative to the amount of local or national economic interactions. The modern Europe-centered world-system became truly Earth-wide in the first half of the nineteenth century when it engulfed the East Asian system. Changes in the magnitude of economic globalization can be estimated by comparing the ratios of the amount of long-distance economic interaction to the size of the global economy. Most efforts to measure changes in the magnitude of structural globalization have compared estimates of the amount of international interaction to estimates of the size of the whole world economy. Usually both the whole world economy gets larger and the amount of international interaction increases, but it is the relative rates of these increases that are understood to be estimates of increasing or decreasing globalization. Deglobalization means that the amount of international interaction decreases relative to the size of the whole world economy.

Early studies that measured structural economic globalization over long periods of time were carried out by economic historian Paul Bairoch (1996; Bairoch and Kozul-Wright 1998). It was Bairoch who discovered that structural economic globalization was a cyclical upward trend with intermittent periods of deglobalization. But Bairoch and most of the other scholars who studied long-term globalization employed rather intermittent temporal estimates that made it difficult to see the timing of changes. [4]

One problem with using international financial statistics for both cross-national quantitative comparisons and for aggregating across nation-states to estimate global characteristics is that is usually necessary to convert country currencies into a single standard that is comparable across countries. Most economic indicators in national accounts are produced in national currencies. To make these comparable across countries or for purposes of aggregation they are usually converted into U.S. dollars, but doing this is problematic. From the Bretton Woods agreements in 1944 until 1971 most country currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, which was theoretically redeemable in gold from Fort Knox, and these rates were mainly set and maintained by national financial authorities (central banks). Since 1971, when the U.S. abandoned the Bretton Woods exchange rate system, exchange rates for country currencies (so-called FX) have been set by the global currency market.

Depending on what the monetary values are intended to indicate, neither pegged nor currency market exchange rates are ideal for standardizing country currencies into a comparable indicator. If one is interested in comparing the availability of goods and services to populations within countries, the use of currency market exchange rates does not do this well because exchange rates among currencies reflect many other things besides the relative value of goods and services in different countries. Kravis, Heston and Summers (1982) sought to correct this problem and to produce comparable estimates of real gross product by weighting GDP figures using a correction for the prices of a basket of typical consumer goods in each country, so-called purchasing power parity or PPP. These corrections were initially estimated for 1980. Korzeniewicz and Moran (1998) noted that PPP weights are unrealistic for studies over long periods of time unless the weights are recalculated for the earlier time periods. Angus Maddison developed a method for estimating PPP values back in time, and he produced a widely used set of international financial statistics that have been used for both cross-national comparisons and for aggregating world totals to estimate the magnitudes of characteristics of the whole world political economy (Maddison 1995).[5]

Maddison's (1995: 227) estimates of total world GDP jumped from 1820 to 1870, and then to 1900, 1913, 1929 and then to 1950. This makes it difficult to see the finer temporal aspects of changes in the level of trade globalization. It would be desirable to have a yearly measure to see whether there were short-term changes and if the time points in other studies are representative or are deviations from the years surrounding them.

Some scholars who want to use monetary quantities to estimate the sizes or the relative economic power of national societies or to estimate global characteristics such global income inequality prefer to use currency market exchange rates (FX) to convert country currency values into U.S dollars because they are more interested in what a government can afford to buy than in the basket of goods provided to residents. Whichever method is used, it is important to understand how available data sets have been produced.[6]

One method of avoiding the issue of how to standardize is to use ratios of country currency characteristics. The country ratios can be compared or aggregated with having to convert into U.S. dollars. The Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer (2000) study of trade globalization did this in order to estimate how the extent of trade globalization had changed from 1820 to 1995. Using statistics in country currencies for national income and for the value of imports from the publications of Brian R. Mitchell (1992; 1993, 1995) Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer calculated the yearly ratios of imports to national income, usually understood as a measure of “trade openness.”[7] They showed that the average of national trade openness scores were arithmetically identical with the ratio to total world imports total world income when the openness scores were weighted by the population sizes of the countries.[8] These are the estimates that were used to produce Figure 1 below.

World Value Chains and Globalization

Most of the indicators of structural economic globalization use data on nation-states to calculate global totals and to compare them with a summed estimate of international interaction. But world-system scholars have long argued that the global economy is composed of transnational commodity chains –networks of linkages among raw material producers, transporters, production processes and final consumers many of which, but not all of which, cross political boundaries (Hopkins and Wallerstein 1986; Bair 2009). The reality of the global economy is that it is a complex network of interactions among all the local, regional, international, world regional and truly Earth-wide individuals, households, neighborhoods, organizations, municipalities, counties, prefectures, nation-states, transnational and supra-national organizations. Using nation-states as the main unit of data ignores the complexity within them, and much of the complexity of transnational linkages. Smuggling has been an important feature of international economic interaction not captured by official trade statistics since states began collecting revenues using import tariffs.

Theorists of global capitalism have emphasized the great wave of transnational reorganization of production and distribution that has occurred since 1970 with inputs to finished goods coming from multiple distant locations, complex financial flows, multinational ownership structures and global circuits of capital.[9] Some scholars have made efforts to conceptualize and measure how national economies are connected with global value chains in order to get a measurement handle on the globalized structure of the world economy (Mahutga 2012, 2018; Mahutga, Roberts and Kwon 2017; OECD 2005, 2010). It is also well-known that official statistics on capital flows and financial assets do not reflect the huge amounts of money that are held in off-shore banking centers for purposes of tax evasion – so-called “dark value” (Clelland 2014; Tyrala 2019).

A recent article critical of the idea of deglobalization by international economic journalists Shawn Donnan and Lauren Leatherby (2019) points out that:

trade data measure shifts in goods by recording products’ value when they leave a port. But the parts in products often come from other countries these days. Even those parts can be made up of parts from elsewhere. That means a more accurate measure of trade and economic relationships involves recording where value is added.

The 2020 World Development Report from the World Bank presents a valuable overview of the methods and conclusions of the study of global value chains. According to the World Bank World Development Report, global value chains (GVCs) account for about 50% of global trade today but have been declining since 2008. They stress the importance of GVCs in combating poverty and stimulating growth in developing countries. But the efficiency of these trade networks come with great risks. The failure of one actor in the value chain affects the entire network. For example, an automobile contains parts from many different countries and these countries depend on each other to produce their share of the automobile. If a country fails to produce enough parts on their end, the whole process is delayed. Global value chains depend on this mutual trust within the network and require complex and progressive forms of cooperation to grow. The rise of trade protectionism threatens the mutual trust among distant producers and reduces the efficiency of production. The World Bank warns of a slump in investor confidence because of these anti-global sentiments and advocates in favor of policies that increase trade incentives and mindfulness of the environment that will allow developing countries to participate in and benefit from GVCs.

The efforts that have been made to study global value chains try to estimate the value-added by national economies to their exports or the amount of value-added to total national output. There have been two major efforts to operationalize global value chains as attributes of national economies. They both rely on global input-output prices provided by the input-output model developed by Wassily Leontief (1974). The OECD estimates value added to national exports while UNIDO (the United Nations Industrial Development Organization) estimates each nation’s domestic value-added output broken down by different economic sectors. The OECD “Trade in Value Added” estimates the amount of bilateral trade that consists of value added by the exporter using Leontief matrix inverses. UNIDO’s measure is how much of the output in a country was produced domestically. It has nothing to do with trade. It is how much in dollars of a given industrial category is produced domestically, regardless of whether it is then exported or consumed locally. OECD’s measure is how much of the exports from a country were produced locally. Some scholars prefer the UNIDO approach for estimating changes in world globalization (e.g. Mahutga 2012, 2018; Mahutga, Roberts and Kwon 2017) because it can be used to produce a more sensible estimate of globalization in the manufacturing sector. Mahutga estimates globalization in the world manufacturing sector by calculating the ratio of world trade [the sum of national exports] to world value added (the sum of the national value added). Mahutga explains that value added is typically double (or more) counted in trade so that the ratio of trade to value added increases dramatically when inputs cross national borders multiple times. The trade in value added concept is less useful for measuring globalization at the world level.

Matthew Mahutga (2012:13) measured the globalization of three industries (electronics, garments, and transportation equipment) at five-year intervals from 1965 to 2000. Globalization of these value chains in operationalized as fragmentation of these global industries as indicated by the ratio of global trade to global value added. When trade goes up faster than value added an industry is more globally fragmented – the proportion of production that is crossing international boundaries has increased relative to total production. Mahutga (2012: Figure 2) finds that garments fragmented the most and that this took place primarily in the 1970s, electronics increased it fragmentation, but not as much as garments, and this occurred mostly in the 1990s, and fragmentation of transportation equipment also went up but less, and this occurred at a steady rate of increase over the whole time period studied.

Summarize the other findings of the research on global value chains, especially with regard to using them as measures of globalization.

While the efforts to construct better measures of globalization based on global value chains have produced a better understanding of economic globalization in recent decades their relevance for comprehending long-term and very recent changes in the magnitude of economic globalization are hampered by the missing estimates for earlier centuries and for recent years. The most recent OECD estimates are only available for 2015, and the UNIDO (2020) estimates for years after 2015 are rather sparse and so it is not yet possible to know how value chains may have plateaued or be becoming less fragmented in recent years.

Trade Globalization and Deglobalization

For studying international trade quantities over long periods of time estimates of the value of imports are more reliable than exports because nation-states long used import tariffs as an important source of revenues and the set up customs bureaucracies to keep records of the value of imports so that they could tax them.

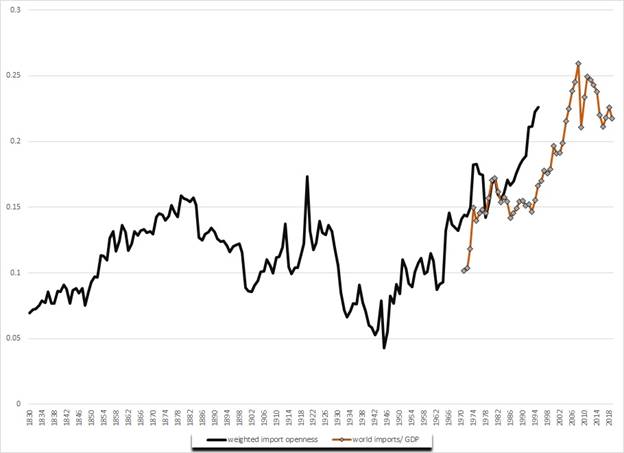

Figure 1: Weighted Average Openness Trade Globalization, 1830-1995 and World Imports/GDP 1971-2019 Sources: Chase-Dunn, Kawano, and Brewer (2000); International Monetary Fund 2020 (imports) World Bank 2020 (GDP)

Figure 1 shows the trade globalization graph based on ratios of the value of imports to the size of national economies that was published in Chase-Dunn et al., (2000). This figure shows the great nineteenth century wave of global trade integration, a short and volatile wave between 1900 and 1929, and the post-1945 upswing that is often characterized as the “stage of global capitalism.” This indicates that, as Paul Bairoch found, structural trade globalization is both a cycle and a bumpy trend, but with a greater degree of temporal resolution. There were significant periods of deglobalization in the late nineteenth century and in the first half of the twentieth century. And there were “plateaus” – periods in which the level of globalization appeared to be oscillating around a stable level, rather than going up or down.

Figure 1 also includes more recent estimates of import globalization from 1971 to 2019 computed from import values from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and GDPs from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. Both are reported in current U.S. dollars.[10]

87)

18.221

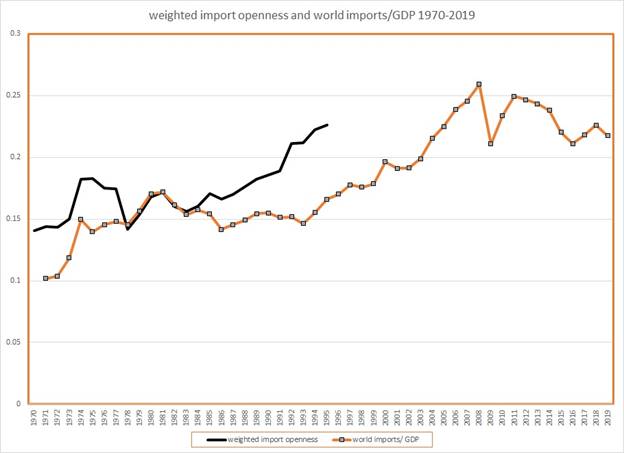

Figure 2: Trade Globalization 1971–2019: World Imports as a Percentage of World GDP Sources: Chase-Dunn, Kawano, and Brewer (2000); International Monetary Fund 2020 (imports) World Bank 2020 (GDP)[11]

The numbers in Figure 2 are the same as the numbers in Figure 1, but the time scale has been shortened so that we may better be able to see what has happened in recent years. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the average openness and the World Bank imports/GDP figures during the overlapping period from 1970 to 1995. The Pearson’s r correlation coefficient between these two indicators during this overlapping period is .73.

There was a drop in the measure of trade globalization (the sum of global imports divided by global GDP) in 2008 and then a recovery but then this indicator fell from 2012 to 2016 and then recovered in 2017 and 2018 and then fell again in 2019. This may indicate that the world-system is entering another period of structural deglobalization, though this in not certain because there have been short-term downturns before that were followed by recoveries of the upward trend since 1945. If indeed we have entered another plateau or another period of deglobalization this has implications for strategies that assumed that structural globalization was going to continue increasing. It is obvious that the COVID 19 pandemic is causing a major contraction in both international trade and in total world output in 2020, but what we do not yet know is whether the trade contraction will be larger or smaller than the output contraction.

The updated series shows a steep decline in the level of global trade globalization during the global financial crisis of 2009 followed by a recovery and then another decline until 2016 and then another recovery in 2017 and 2018 and then another drop in 2019. If we examine the two components of the ratio between world imports and world GDP separately it can be seen that increases in the ratio (trade globalization) occur because imports grow faster than GDP, which is total world economic activity, and decreases occur when GDP grows faster or decreases slower than imports. Both GDP and imports turned down in 2009, but imports fell more, causing a dip in the ratio. The apparent plateauing since 2009 is occurring in a period in which both imports and GDP are still growing but GDP is growing faster than imports (see also Figure A1 in the Appendix).[12]

The long-term upward trend in trade globalization since World War II has been bumpy, with occasional downturns like the one in the 1970s. But the downturns since 1945 have all been followed by upturns that restored the overall upward trend of trade globalization. Figure 2 shows the large decrease of trade globalization in the wake of the global financial meltdown of 2008. This was a 21% decrease from the previous year, the largest reversal in trade globalization since World War II. But the ratio of imports to global GDP increased again in 2017 and in 2018. The question is whether the sharp decrease after the financial meltdown was the beginning of a new reversal in the long upward trend over the past half century or just another hiccup. It should be noted that this indicator of economic globalization has not yet reached the level that it had in 2008. Bond (2018), Van de Bergeijk (2010, 2018a, 2018b); Bond 2017 and Witt (2019) have argued that the world-system has already entered another phase of deglobalization.

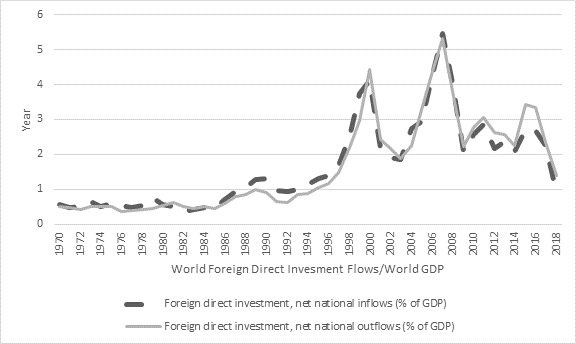

Investment Globalization and Deglobalization

The ratio of global investment flows to the size of the global economy provides additional evidence that the world economy may have entered another period of deglobalization (Figure 3).[13] The ratio of international investment flows to the global GDP took a dive in the late 1990’s, recovered and then took another dive in 2007, which was followed by a weak recovery and then another dive in 2018. So, this indicator implies that a deglobalization phase may have been entered. The results for 2020 will probably not be published by the World Bank until late summer of 2021.

Figure 3: Investment Globalization 1970–2018: World Foreign Direct Investment Flows as a Percentage of World GDP: Source: World Bank (2019) World Development Indicators

Add section presenting and discussing formal network analysis results for the global trade and investment matrices.

Add section discussing tourism and protectionism measures. Also discuss communications connectivity trends

Comparing Plateaus and Deglobalization Phases in World History

Our next task is to designate periods of deglobalization and plateaus in the upward trend of trade globalization over the past two centuries using the estimates we have of the degree to which the

world political economy of the Europe-centered world-system was globalized. Tthe whole system was expanding in the first half of the 19th century as the European powers surrounded China and incorporated the East Asian world-system into the now-global modern world-system. This was a powerful instance of globalization that resulted in the formation of a single Earth-wide (global) world-system for the first time. But we may also be able use economic statistics to estimate changes in the size of international trade relative to the size of the whole world economy in the period before the incorporation of East Asia. For studying the 19th century we will rely on the measure of weighted average trade openness developed by Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer (2000) keeping in mind however that the estimates we have for average openness were based on a very small number of national economies for the early 19th century. Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer extensively examined the relationships between the results based on their growing number of national openness estimates and the total world estimates produced by Maddison.[14] Figure 1 uses the Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer estimates from 1830 to 1995 and the World Bank estimates used in Figure 2 from 1971 to 2019. The average trade openness and World Bank estimates overlap from 1970 to 1995, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

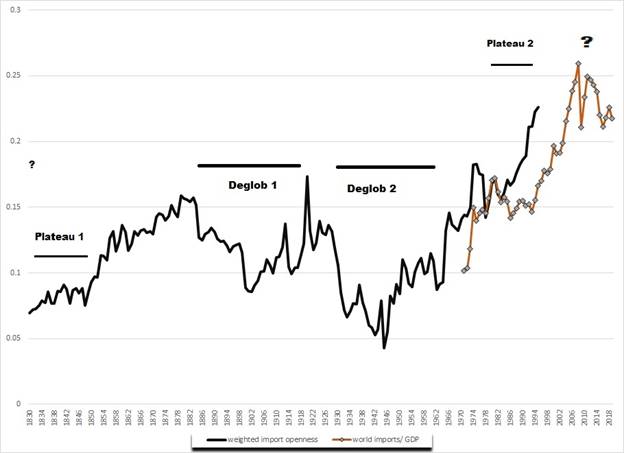

Figure 4 is the same as Figure 1 except that plateaus and phases of deglobalization have been added.

Figure 4: Plateaus and Deglobalization Phases in the 19th, 20th and 21st Centuries (same Figure as 1)

Regarding phases of deglobalization within the Europe-centered system, there may have been three since 1791. The first is indicated by the big decrease in the relationship between the value of imports and the national income of the early United States brought on by the Napoleonic Wars in which the embryonic First New Nation fought off an effort by the United Kingdom of Great Britain to reclaim its lost colonies in North America.[15] Was this first period of import openness followed by import closure in the United States a pattern typical of the other states in the Europe-centered system? We know that interimperial rivalry between France and the United Kingdom had made trade and access to raw materials an important part of global warfare. The colonial systems of the contending powers were important players in the struggle, as was made obvious by both the American and the Haitian revolutions. The U.S. was probably not a typical case because, except for Haiti, the other colonies did not gain independence until the 1820s. We do not know whether there was an early 19th phase of deglobalization. A lot was shaking in what has been called the World Revolution of 1789 and there were undoubted contractions in both total output and in trade, but we are not sure about the relationship between these in this period.

By 1830 we have quantitative estimates of imports and GDP for three countries, the United States, France, and Great Britain. By 1861 we add Australia, Denmark, Italy, and Sweden for a total of seven countries. The fourth group (fourteen countries), begins in 1905, adding Cuba, Spain, India, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, and Taiwan. The fifth group (24 countries) begins in 1927 and adds Austria, Canada, Colombia, Greece, Guatemala, Honduras, Hungary, Indonesia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. The sixth group (50 countries), begins in 1950 and the seventh group with 89 countries begins in 1965.

Deglob 1: Financial Panics and the Great Recession

The first relatively certain period of deglobalization, using peaks to peaks as an indicator, is from 1883 to a trough in 1902, and a partial recovery peaking in 1913. Then there was another plunge with the arrival of World War I that troughed in 1915, and then a recovery to a peak in 1920. This is labeled as Deglob 1 in Figure 4. The run-up to Deglob 1 began with the financial panic of 1873 in Europe and North America, but the decline in trade globalization did not occur until the panic of 1883. The whole period from 1873 to 1897 has been called the Long Depression.

In the decades of the late 19th century challengers to British hegemony were emerging as

other core states industrialized. German unification and the rise the United States to core status in the 1880s led to a less unicentric structure of economic and military power within the core. In 1884 the British organized the Berlin Conference on Africa, which divided that continent up into European colonies. This was an effort by the British to include Germany in the club of colonial empires as a cooperating ally rather than as a hegemonic challenger. Thus, another wave of European colonialism was contemporaneous with the period of deglobalization that emerged in the late 1`9th century (See Figure A3 in the Appendix.)

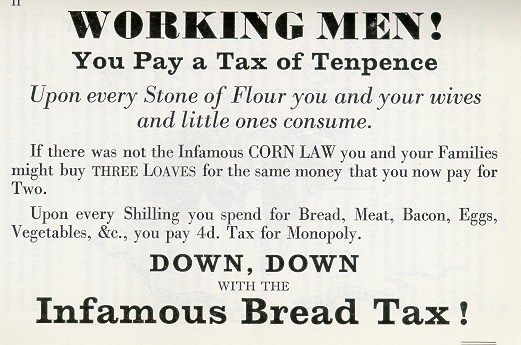

Paul Bairoch (1993) noted that the period between 1815 and 1860 was one in which the British opened their home market to foreign goods and advocated that other countries should do the same. This was the heyday of Cobden and Bright and their Anti-Corn Law League.[16] But it was only between 1860 and 1879 that other countries on the European continent decreased their tariff barriers to imports. The United States adopted greater tariff protection following the northern victory in the U.S. Civil War. After 1879 the European states gradually slipped back toward protectionism, while the British maintained low tariffs until 1914 despite huge political arguments over this policy (Taylor 1996). Bairoch (1993:51) shows that the reintroduction of protectionism did not have a long-term negative affect on the growth of exports for those countries that went protectionist. One of the big differences between Deglob1, Deglob 2 and the contemporary period is in the configuration of politics of the Left and Right (Chase-Dunn and Almeida 2020). In Deglob1 the labor movement was on the rise, becoming active in politics in many core states at the beginning of the 20th century. In Britain this produced the “social imperialism” and protectionism of Joseph Chamberlain in which redistributive polices were combined with an effort to protect jobs through tariffs and to revitalize and further expand the empire. This provides an interesting comparison with Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again.”

According to Bairoch in the second decade following their reintroduction of protectionism France, Germany, Italy, Denmark, and Switzerland all had higher rates of export growth than in the decade before they went protectionist, and this was also true for Europe as a whole. The United Kingdom, where a liberal trade policy was maintained, had a declining rate of export growth over this same general period. Bairoch did not go so far as to claim that protectionism causes globalization, but he does assert and support the contention that trade liberalization did not cause globalization in the late nineteenth century.

Figure 5: Anti-Corn Law League Poster

Our average openness measure of world-level trade globalization is similarly contradictory with the hypothesis that trade liberalization causes globalization and protectionism causes deglobalization. The first wave of trade globalization began well before the European shift toward free trade. And the downturn in the early 1880s preceded by several years the readoption of protectionism policies by the European states.[17] There was an economic recovery but then World War I caused trade deglobalization, which was then followed by a recovery after the war that peaked in 1920. The wobbly wave of globalization from 1901 to 1929 was a discovery made by the Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer (2000) study. They found three waves of globalization, one in middle of the 19th century, the wave after World War II, and this partial wobbly wave during the first decades of the 20th century.

Another round of deglobalization began in 1921, but then there was a recovery during the 1920s followed by the great crash of 1929 that ushered in another wave of protectionism and deglobalization. The trough of Deglob 2 was in 1942 when the world economy reached a point of trade deglobalization well below that of the trough of Deglob 1.

Deglob 2: Stock Market Crash of 1929, Another Great Depression

Deglob2 began with the stock market crash of 1929. It’s trough was in 1942 and the connectedness of world trade did not recover to the 1928 level until 1974. Other studies that compare the current period of possible deglobalization with earlier periods all focus in the 1930s (Deglob 2) but do not compare with Deglob1 (Van Bergeijk, 2010; 2018a; 2018b; O’Rourke 2018). They note that both Deglob2 and the current period were triggered by a financial collapse. This was also true of Deglob 1.

Despite the common belief that the economic collapse of the 1930s was caused by protectionism, Bairoch (1993) shows that protectionism was not particularly high in the 1920s and the Smoot-Hawley tariff was adopted in the U.S. after the stock market crash of 1929 and after the decline in trade globalization had already begun. The rise of the middle wave occurred during a period in which tariffs were high but not rising or falling, and the rising tariffs of the 1930s occurred after trade globalization had already begun to fall.

The third wave of globalization after World War II began well before the trade liberalization advocated by the now-hegemonic U.S. had been adopted by many countries. The greater trade openness of the peripheral countries subjected to International Monetary Fund structural adjustment since the 1980s has generally occurred in a period of very slow GDP growth. The countries that grew during the "Asian miracle" period on the basis of export promotion did contribute to the rise of trade globalization and their successes were largely due to their access to the U.S. market, so trade liberalization in the last decades of the 20th century probably had a positive impact on the level of trade globalization. But the cycles of trade globalization and deglobalization over the long run do not correspond very closely with changes in the degree of international trade liberalization.

The political configuration of movements and parties in geoculture had evolved considerably since the Deglob1. Now the Global Left was ensconced in labor and socialist parties in many states, and Communists had taken state power in the Soviet Union in the World Revolution of 1917. The new kid on the block was fascism, a form of virulent and authoritarian nationalism that had been emerging since the turn of the century, but that had taken state power in several countries by the time of the Deglob2 (Chase-Dunn, Grimes and Anderson 2019; Chase-Dunn and Almeida 2020).

Kevin H. O’Rourke’s (2018) comparison of the similarities and differences between the current period with the Great Depression of the 1930s (Deglob 2) points out that colonial empires still existed in the 1930s and he shows that international trade became more segmented during the Great Depression as core states traded with one another less and increased trade with their own colonies (O’Rourke 2018: Table 1). After the great wave of decolonizations that occurred from World War II until the 1960, formal colonialism ceased to be part of the structure of global governance. O’Rourke contends that this is an important difference between Deglob 2 and the current period, but it is also possible that the functional equivalent of colonial empires continues to exist as neo-colonial structures of control between international organizations and core states and “their” bilateral connections with non-core regions. The attacks on the World Trade Organization by the Global Justice movement in Seattle in 1999 and Cancun in 200x caused a retreat from efforts to structure North-South relations through multilateral agencies, and an embrace of bilateral trade deals that are somewhat reminiscent of the formal colonial empires that existed during Deglob 2. Whether or not this trend and be seen in the global trade network is a question that we are trying to answer (see Kim 2020).[18]

Again the constellation of movements and parties in the geoculture is different from what existed in the earlier waves of deglobalization. Some of the old movements are still around but have evolved under different economic structural and political conditions, and new movements have emerged. The culture of the Global Left was reconstituted in the World Revolution of 1968 in which student in the New Left criticized the parties and unions of the Old Left for the failures of the World Revolution of 1917. A new communitarian and anarchistic individualism and participatory forms of democracy supported a critique of all forms of organizational hierarchy and supported horizontalism. Global indigenism and a critique of Eurocentrism were central tropes of the Global Justice movement that emerged with the World Social Forum in 2001. On the right, populist authoritarianism and racial nationalism, similar in some ways to the fascism of the 20th century, emerged as a substantial political force in many countries in reaction to the neoliberal globalization project (Rodrik 2018; Chase-Dunn, Grimes and Anderson 2019)

Some Leftist activists see the coming period of deglobalization as an opportunity for the Global South. In earlier periods of interruption of core/periphery relations development projects in the Global South were able to make headway. There has always been a tension within the New Global Left regarding anti-globalization versus the idea of an alternative progressive form of globalization. Samir Amin (1990) and Waldon Bello (2002) are important progressive advocates of deglobalization and delinking of the Global South from the Global North to protect against neo-imperialism and to make possible self-reliant and egalitarian development. Alter-globalization advocates an egalitarian world society that is integrated but without exploitation and domination. The alter-globalization project has been studied and advocated by Geoffrey Pleyers (2011) as an “uneasy convergence” of largely horizontalist autonomous and independent activist groups and more institutionalist actors like intellectuals and NGOs.

How can we explain the trajectory of trade globalization and deglobalization? For globalization there are two things that need to be explained: the trend and the cycles. For the trend, the falling costs of transportation and communications must be a main driving force of the upsurges of globalization. But these declining costs of long-distance transport and communications are facilitating background factors that cannot explain the periods of deglobalization because costs did not radically increase when globalization declined.

To explain cycles, we must find causes that are themselves cyclical. How have the cycles of globalization and deglobalization corresponded with other known cycles in the global political economy? Can we assume that the causes of upswings are the same as the causes of downswings, except in reverse? That would simplify things, but the example of transportation and communications costs just mentioned implies that things may not be so simple.

How do the ups and downs of economic globalization correspond temporally with other known cycles? Causality should be revealed in the temporal relationships among variables. The contenders here are business cycles (increases and decreases is the rates of economic growth and trade (the Kuznets cycle and the Kondratieff Wave), profit squeezes, waves of colonization and of decolonization, the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers (the hegemonic sequence), failures of global governance due to weakened international institutions, rise of authoritarian regimes, waves of immigration, anti-immigrant movements, uneven development, the war wave, and the incidence of world wars, the debt cycle and changes in the level of trade protectionism, changes in the terms of trade and the prices of raw materials produced in the Global South, demographic shifts in age distributions and growth rates.

The hegemonic sequence has been quantitatively measured in terms of military power (or rather naval and air power) by Modelski and Thompson (1988). They examine the proportion of intercontinental power capability that is controlled by the most powerful country. In the period we are studying they find the rise and decline of Britain in the nineteenth century and the rise of the United States in the twentieth century. The world-systems perspective has emphasized the importance of economic power in the hegemonic sequence. These two approaches have influenced each other and Modelski and Thompson (1994) included economic power as an important part of their conceptualization and measurement of "global leadership." Arrighi (1994) recognized the importance of ideology and legitimacy in the successful performance of the hegemonic role

Regarding the problem at hand, both the first and the third waves of globalization correspond to the rise and consolidation of hegemonies, the British in the nineteenth century and the U.S. after World War II. But the middle wave, that rose from about 1900 through the 1920s, occurred in a period in which hegemony was being radically contested. This middle wave cannot be a function of hegemonic rise and fall because there was no rise or fall in this period, but its wobbly nature and its shortness may have been partly due to the absence of a hegemon.

The Kuznets business cycle is a twenty-year cycle in which economic growth increases for about ten years and then stagnates for about ten years. This is too short a period to account for the waves of globalization and deglobalization. The Kondratieff Wave is a longer business cycle that varies from 40 to 60 years. This is a closer match to the waves of globalization. The 1929 crash fits with the decline of the second wave and the start of Deglob 2. But there are some non-fits as well. The period of the Great Depression of the 1870s was during the latter part of the rise of the first wave of trade globalization, which did not begin its decline until the 1880s. Most K-wave studies find a K-wave decline (B-phase) beginning in about 1970. This one is not associated with a drop in globalization. Indeed after 1975 our measure indicates a rise to the highest level of globalization known, though this is due mostly to the increasing openness of non-core countries.

World Wars do not fit well with the three waves of globalization, nor with the deglobalizations. The only data we have prior to. and during, the Napoleonic War is from the U.S., and they are unreliable as a basis for studying trade globalization and deglobalization. After the Napoleonic Wars there were no world wars in the nineteenth century in the sense of major wars among core powers. There were three "Great Power Wars" between 1815 and 1914, but none of them were very big (Levy 1983:72-3). World War I was during the first rise of the middle wave of globalization. World War II began before the trough of the middle wave and ended before the beginning of the rise the third wave of globalization. There is no regular relationship between world wars and the globalization cycles.

Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Things That Need Further Research

We have contributed to the research literature on deglobalization phases by adding comparisons with the Deglob 1 in the late 19th century. Table 1 summarizes some of the similarities and differences across the two phases of deglobalization and the current period in which the world-system may have entered another phase of deglobalization.

|

|

Deglob 1 |

Deglob 2 |

Current Period |

|

1. Hegemonic decline (rising challengers) |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

2. World Wars |

no |

yes |

no |

|

3. Colonial expansion |

yes |

yes |

no |

|

4. Rising nationalism |

yes |

yes |

Yes |

|

5. Rising decolonization |

yes |

yes |

no |

|

6. Triggered by financial crisis |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

7. Economic slowdown |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

8. Rising Protectionism |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

9. Heightened competition among core states and firms |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

10. Rising authoritarianism |

no |

yes |

yes |

|

11. Rising immigration |

yes |

no |

yes |

|

12. Anti-immigrant movements |

yes |

yes |

yes |

|

13. ? |

|

|

|

Table 1: Similarities and Differences between Phases of Deglobalization

Regarding the question of causation, some of the similarities across all three periods, such as trade protectionism, have been disputed as causes (see discussion of Bairoch above). Contemporaneity does not prove causation. Of the twelve systemic characteristics listed in Table 1, seven are present in all the deglobalization phases. These are hegemonic decline and rising challengers, rising nationalism, a financial crisis trigger, economic slowdown, rising protectionism, heightened competition among core states and firms, and anti-immigrant movements. The five systemic characteristics that present for some, but not all, of the phases are world wars, colonial expansion, rising decolonization, rising authoritarianism, and rising immigration. Of course, we know that a given kind of historical outcome may have different causes, so consistency or inconsistency does not rule out a systemic condition as a possible cause. For example, as discussed above, colonial empires were abolished in the post-World War II global order, but functional equivalents of colonial relationships continued to exist and it may be that the most recent phase of possible decolonization has been accompanied by a resegmentation of the trading relationships between core states and sets of non-core regions. This is a hypothesis that we plan to investigate soon and will report the results in a revise version of this paper.

The world-system is probably entering another phase of deglobalization, although a recovery of the upward trend in connectedness after recovery from the COVID19 crisis. The main causes of deglobalization are probably mainly tied to the contradictions of global capitalism and an emerging crisis of global governance as the U.S. economic hegemony continues to decline. Increasing competition between core states and a coming period of military multipolarity will make another period of economic deglobalization more likely.

We conclude that it is likely that the world-system is reentering another phase of deglobalization, but this is by no means yet certain. After the current output and international trade downturn there will be a recovery. Will that recovery be followed by a return to the upward trend toward greater integration or will it continue as a plateau or will it trend downward into another phase of deglobalization? This is not be known for sure for at least five years from now. In the mean time we can further develop and test hypotheses about the causes and consequences of earlier phases of deglobalization, and we can begin to systematically study the causes and consequences of trade expansions and contractions for sociocultural evolution by comparing the modern world-system with earlier regional world-systems.

Is the global network of trade and investment becoming more segmented into individual core states increasing their ties with non-core regions, as happened in both earlier phases of deglobalization? This question can be answered by studying recent changes in the structure of the international networks of trade and investment. Have global value chains in industrial sectors continued to become more fragmented by increased sourcing of inputs from abroad, or has this trend plateaued or even decreased in recent years. Updated measures and more complete coverage of countries will make it possible to answer this question.

References

Amin, Samir. 1990. Delinking: Towards a Polycentric World. London: Zed Books.

Arase, David 2020 “China’s Rise, Deglobalization and the Future of Indo-Pacific Governance” Asia Global Papers, No, 2, July https://www.asiaglobalinstitute.hku.hk/storage/app/media/AsiaGlobal%20Papers/chinas-rise-deglobalization-future-of-indo-pacific-governancedavid-arase.pdf?utm_source=Asia+Global+Institute&utm_campaign=a8829a189e-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_07_30_05_43&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_c139173191-a8829a189e-

Arrighi, Giovanni. 1994 The Long Twentieth Century. London: Verso.

——. 2006. Adam Smith in Beijing. London: Verso

—— and Beverly Silver. 1999. Chaos and Governance in the Modern World-System: Comparing Hegemonic Transitions. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bairoch, Paul 1996 “Globalization Myths and Realities: One Century of External Trade and Foreign

Investment”, in Robert Boyer and Daniel Drache (eds.) , States Against Markets: The Limits of

Globalization, London and New York: Routledge.

Bair, Jennifer, ed. 2009 Frontiers of Commodity Chains Research. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University

Press.

Bairoch, Paul and Richard Kozul-Wright 1998 “Globalization myths: some historical reflections on

integration, industrialization and growth in the world economy,” pp.37-68 in Richard Kozul-

Wright and Robert Rowthorn (eds.) Transnational Corporations and the Global Economy. London: MacMillan

Bello, Walden. 2002. Deglobalization. London: Zed Books.

Bond, Patrick 2018 “East-West/North-South – or imperial-subimperial?: The BRICS, global

governance and capital accumulation” Human Geography 11,2

Brady, David, Jason Beckfield and Wei Zhao. 2007. “The Consequences of Economic Globalization

for Affluent Democracies.” Annual Review of Sociology 33:313-334.

Bromley, Patricia, Evan Schofer, Wesley Longhofer 2020 “Contentions over World Culture: The

Rise of Legal Restrictions on Foreign Funding to NGOs, 1994–2015” Social Forces, Volume 99, Issue 1:281–304, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soz138

Chase-Dunn, C. 1978. "Core-periphery relations: the effects of core competition," in Barbara H.

Kaplan (ed.) Social Change in the Capitalist World Economy. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Chase-Dunn, C. 1998 Global Formation: Structures of The World-Economy. Lanham, MD: Rowman and

Littlefield.

Chase-Dunn, C. 1999 “Globalization: a world-systems perspective,” Journal of World-Systems

Research 5,2, 186-216. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.1999.134

Chase-Dunn, C and Kelly M. Mann 1996 The Wintu and Their Neighbors: A Very Small World-

System in Northern California. Tucson: University of Arizona Press

Chase-Dunn, C., Yukio Kawano and Benjamin Brewer 2000 “Trade globalization since 1795:

waves of integration in the world-system” American Sociological Review 65, 1: 77-95.

https://wsarch.ucr.edu/archive/papers/c-d&hall/isa99b/isa99b.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. and Andrew Jorgenson 2007 “Trajectories of trade and investment globalization” Pp. 165-185 in Ino Rossi (ed.) Frontiers of Globalization Research: Theoretical and Methodological Approaches. New York: Springer https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows10/irows10.htm

Chase-Dunn, C,, Roy Kwon, Kirk Lawrence and Hiroko Inoue 2011 “Last of the hegemons: U.S.

decline and global governance” International Review of Modern Sociology 37,1: 1-29 (Spring).

https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows65/irows65.htm

Chase-Dunn, C. and Bruce Lerro 2014 Social Change: Globalization from the Stone Age to the Present.

London: Routledge

Chase-Dunn, C. Peter Grimes and E.N Anderson 2019, “Cyclical Evolution of the Global Right”

Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie, 56: 529-555. doi:10.1111/cars.12263

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cars.12263

Chase-Dunn, C and Paul Almeida 2020 Global Struggles and Social Change. Baltimore, MD: Johns

Clelland, Don A. 2014 “The Core of the Apple: Degrees of Monopoly and Dark Value in Global

Commodity Chains”. Journal of World-Systems Research, 20(1), 82-111. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2014.564

Donnan, Shawn and Lauren Leatherby 2019 “Globalization Isn’t Dying, It’s Just Evolving”

Bloomberg.com July 23, 2019 https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2019-globalization/?srnd=economics-vp

Eichengreen, B., & O’rourke, K. H. (2009). A tale of two depressions. VoxEU. Org, 1.

World Bank 2019. World Development Indicators [online]. Washington DC: World Bank.

http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators

Hamashita, Takeshi 2003 “Tribute and treaties: maritime Asia and treaty port eglobal in the era of

negotiations, 1800-1900” Pp. 17-50 in Giovanni Arrighi, Takeshi Hamashita and Mark Selden (eds.) The Resurgence of East Asia. London: Routledge

Harvey, David 2005 A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York; Oxford University Press

Hopkins, Terence K., and Immanuel Wallerstein 1986 “Commodity Chains in the World-Economy

Prior to 1800” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 157-170 https://www.jstor.org/stable/40241052

International Monetary Fund (IMF) Direction of Trade Statistics 2020

https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61013712

Kim, Jisoo 2020 “Deglobalization and Global Value Chains in the Core of the World-System”

IROWS Working Paper # 138 at https://irows.ucr.edu/papers/irows138/irows138.htm

Korzeniewicz, R. P., Moran, T. P., & Consiglio, D. 1998 “Global Divergence Since 1820:

Challenging the Consensus” Department of Sociology, University of Maryland, College Park,

Maryland. Unpublished manuscript.

Kravis, Irving B., Alan Heston and Robert Summers 1982 World Product and Income: International

Comparisons of Real Gross Product. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Leontief, Wassily 1974 “Structure of the world economy: outline of a simple input-output

formulation”. The American Economic Review, 823-834

Levy, Jack S. 1983 War in the Modern Great Power System, 1495-1975. Lexington:

University Press of Kentucky.

Maddison, Angus 1995 Monitoring the World Economy, 1820-1992. Paris: OECD

Mahutga, Matthew C. 2012. “When Do Value Chains Go Global? A Theory of the Spatialization of

ValueChain Linkages.” Global Networks 12(1):1–21.

Mahutga, Matthew C,. Anthony Roberts and Ronald Kwon 2017 “The Globalization of Production

and Income Inequality in Rich Democracies” Social Forces 96(1) 181–214, September 2017

Mahutga, Matthew C,. 2018 “Global value chains and quantitative macro-comparative sociology”

Pp. 91-104 in Stefano Ponte, Gary Gereffi and Gale Raj-Reichert (eds.) Handbook on Global

Value Chains. Northhampton, MA: Edward Elgar

Mann, Michael 2012 The Sources of Social Power, Volume 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mc Michael, Phillip 2017 Development and Social Change. Thousand Oaks, CA; Sage.

Meyer, John W. 2009. World Society: The Writings of John W. Meyer. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Mitchell, Brian R. 1992. International Historical Statistics: Europe 1750-1988. 3rd edition. New York: Stockton.

Mitchell, Brian R. 1993. International Historical Statistics: The Americas 1750-1988. 2nd edition. New York: Stockton.

Mitchell, Brian R. 1995. International Historical Statistics: Africa, Asia, and Oceania 1750-1988. 2nd edition. New York: Stockton.

Modelski, George. 2005. “Long-Term Trends in Global Politics.” Journal of World-Systems Research. 11(2): 195-206.Modelski, George and William R. Thompson 1988 Seapower in Global Politics, 1494-1943. Seattle:

University of Washington Press.

____________________________________1994 Leading Sectors and World Powers: the Coevolution of

Global Economics and Politics. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

O’Rourke, Kevin H. 2018 “Two Great Trade Collapses: The Interwar Period and Great Recession

Compared”. IMF Economic Review. 66 (3): 418–439. doi:10.1057/s41308-017-0046-0.

O’Rourke, Kevin H., and Jeffrey G. Williamson 2002 "When Did Globalisation Begin?" European

Review of Economic History 6 (1): 23–50.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) 2005 Measuring Globalisation: OECD Economic Globalisation Indicators 2005 https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/measuringglobalisationoecdeconomicglobalisationindicators2005.htm

OECD 2010 Measuring Globalisation: OECD Economic Globalisation Indicators, Paris: OECD

https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/measuringglobalisationoecdeconomicglobalisationindicators2010.htm

Pleyers, Geoffrey (2011). Alter-Globalization. Malden, MA: Polity Press

Robinson, William I. 2019 Into the Tempest: Essays on the New Global Capitalism. Chicago: Haymarket

Rodrik, Dani. 2018. “Populism and the Economics of Globalization.” Journal of International Business Policy DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-018-001-4

Smith, David A. and Douglas White 1992 "Structure and dynamics of the global economy: network

analysis of international trade, 1965-1980." Social Forces 70,4:857-893.

Taylor; Peter J. 1996 The Way the Modern World Works: World Hegemony to World Impasse New York:

Wiley.

Tilly, Charles. 1995. “Globalization Threatens Labor’s Rights.” International Labor and Working-Class History 47(Spring):1– 23.

Tyrala, Michael 2019 “Accumulation by Taxploitation: A World-Systems Analysis of Offshore Tax

Dodging and its Evolving Impact on the Capitalist World-Economy. Unpublished PhD dissertation. City University of Hong Kong

UNIDO INDSTAT2 - UNIDO Industrial Statistics Database 2020 edition at the 2-digit level of ISIC (Revision 3) https://stat.unido.org/metadata

Van Bergeijk, Peter A.G. 2010 On the Brink of Deglobalization: An Alternative Perspective on the Causes of

the World Trade Collapse. Cheltenham Glos GL50 2JA UK: Edward Elgar

___________________ 2018a ‘On the brink of deglobalization…again’, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society rsx023. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx023

___________________ 2018b “Deglobalisation 2.0: Trump and Brexit are but symptoms” (March

13) Deglobalisation Series https://issblog.nl/2018/03/13/deglobalisation-series-deglobalisation-2-0-trump-and-brexit-are-but-symptoms-by-peter-a-g-van-bergeijk/

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1984 “The three instances of hegemony in the history of the

capitalist world-economy.” Pp. 100-108 in Gerhard Lenski (ed.) Current Issues and

Research in Macrosociology, International Studies in Sociology and Social

Anthropology, Vol. 37. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

________________ 2003 The Decline of American Power. New York: New Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2012. The Modern World- System, vol. 4. Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press.

Witt, Michael A. 2019 “De-globalization: theories, predictions and opportunities for international business research” Journal of International Business Studies Volume 50, Issue 7, pp 1053–1077| https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41267-019-00219-7

World Bank 2019. World Development Indicators [online]. Washington DC.

https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#

World Bank 2020 World Development Report: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains.

https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2020

World Trade Organization 2019 Global Value Chain Development Report 2019: Technological Innovation,

Supply Chain Trade and Workers in a Globalized World. Geneva: WTO

____________________ 2020 “Trade set to plunge as COVID-19 pandemic upends global

economy” Press Release 20-2749, April 6.

Xu, Yingying 2012 “Understanding International Trade in an Era of Globalization: A Value-Added

Approach” MAPI.net 1600 Wilson Blvd Suite 1100, Arlington, VA 22209